EPA Grants Fund Researchers Working with Communities to Monitor Air Pollution in Washington and Pennsylvania

Posted September 10, 2018

Reducing air pollution levels takes the effort of an entire community. At least that’s the opinion of Catherine Karr, a professor at the University of Washington (UW), and principal investigator of an air pollution study in the lower Yakima Valley in Washington State.

This agricultural valley has historically experienced high levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), a common air pollutant, especially in the winter during cold stagnant air periods. Major sources of PM2.5 include residential wood-burning heaters and agricultural burning. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 can cause respiratory and cardiovascular illness and lead to decreased lung function, irregular heartbeat, atherosclerosis (narrowing of the arteries) and premature death.

Dr. Karr’s air pollution study is funded by an Air Pollution Monitoring in for Communities grant from EPA’s Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Program. The grants, awarded to six universities and research institutions across the country, are providing researchers with the opportunity to investigate emerging air monitoring technology and to work with communities to address air quality problems. While low-cost and portable air sensor technology is becoming readily available to the public, there is limited knowledge on how communities and individuals are using the technology, the accuracy of the data they produce, how the sensors perform over time, and what is needed to help inform future sensor use.

To evaluate the use of low-cost air pollution sensors by communities, research scientists at the UW are partnering with Heritage University. Heritage students reflect the diversity of the community, including Yakama Nation, Native Americans of other tribes, and Latino immigrant families.

As part of the study, researchers teach the students how to use low-cost air pollution sensors to monitor air quality. They use this knowledge to work with local high school students to conduct citizen science projects to investigate PM2.5 exposure--and exposure to wood smoke in particular--in their communities. The students learn about air quality issues and share what they learn with their families, tribal elders, and others in their community, helping to increase community awareness of air pollution issues and air sensor technologies.

“Students are a good bridge to the community at large,” says Karr. “Not only do they help us by collecting data, but we can also provide an opportunity for them to explore some related fields, see science in action and get to know the scientists.”

The researchers are working with many groups including the Air Quality Section of the Yakama Nation Environmental Management Program, education leaders and other community organizations to identify potential solutions for reducing fine particle pollution. This collaboration helps incorporate many perspectives into the project and ensures that the results will be meaningful to the decision-makers.

“It’s so important to have these conversations where everybody feels their perspective is respected and understood,” says Karr. “Building that relationship and trust with a community is critical to being able to improve local air quality.”

Across the country, another STAR grantee at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) is working with residents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a city that has struggled with exposure to air pollution for many years. In 2017, an American Lung Association study ranked the area encompassing Pittsburgh and the surrounding areas as eighth-highest in a list of 200 metropolitan areas in the country for long-term soot pollution.

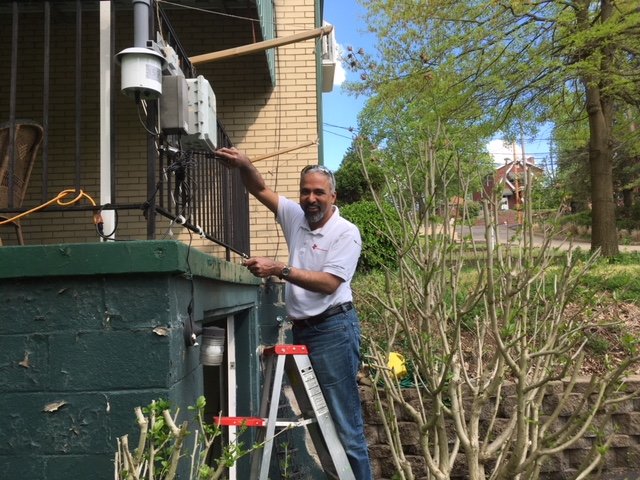

Dr. R. Subramanian, a research scientist in CMU’s mechanical engineering department and the principal investigator for this project, has provided communities in Pittsburgh with real-time affordable multi-pollutant (RAMP) air quality monitors to measure local pollutant levels. The monitors have been distributed throughout the city, with some hosted at the homes of local citizens. CMU researchers have a series of goals, one of which is examining whether communities are empowered to take action when they have information about air quality from sensors and air pollution maps that show risks of exposure. Researchers are also looking to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of these low-cost sensors.

RAMP monitors installed in Pittsburgh measure common air pollutants, including PM2.5, ozone, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide, all of which can impact human health.

“We have air scientists, social scientists, community organizations, public-private partnerships, and of course, the people of Pittsburgh who have hosted the RAMPs and have been very engaged about air pollution issues,” Subramanian says. “I think that level of collaboration is more of what’s needed to bring about meaningful lasting change.”