Study Shows Some Household Materials Burned in Wildfires Can be More Toxic Than Others

Published March 1, 2022

On Dec. 30, 2021, a wildfire between Denver and Boulder, Colorado, burned more than 1,000 houses and other structures, making it the most destructive fire for property damage in the history of the state. In addition to the losses, the area was filled with smoke from burning wood, plastics, and many types of human-made materials.

Researchers at EPA want to know how smoke toxicity from these urban fires compares to smoke from fires fueled solely by trees and other vegetation. At the same time, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) is interested in the potential health effects from open burn pits that were used to destroy tons of waste at military bases in Iraq and Afghanistan. While the practice has been banned, many military and civilian personnel have since experienced asthma, pneumonia, bronchitis and other lung conditions that have been linked to air pollution in and near military bases, although further information is needed to determine direct causation.

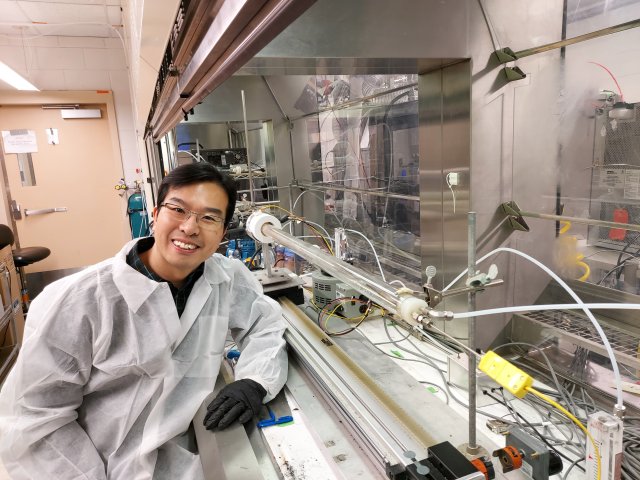

The two interests have merged in a laboratory at EPA’s Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, where a unique combustion system developed by EPA is making it possible to obtain near real-world results on the health effects of smoke from wildfires and prescribed fires (see related links). The study was done in collaboration with researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and The Netherlands Organisation of Applied Sciences.

“Our study can help to better understand the health effects of combustion smoke from dwellings in the wildland urban interface (WUI) during a wildfire,” explains Yong Ho Kim, lead author on the study.1 “Wildfires are bad but the burning of synthetic materials like plastic can make it worse.”

The World Health Organization has reported that when wildfires impact urban areas, the materials burned contain more toxic chemicals than from wildfires that consume wood and other natural materials. Using a laboratory scale combustion system to produce smoke, EPA researchers have the ability to quickly conduct controlled studies on toxic outcomes of different types of materials burned.

For the study, researchers simulated burnpit fires using five different materials – military grade cardboard and plywood, several common types of plastic, a mixture of materials, and a mixture with diesel fuel, often used as a fire accelerant. Each type of waste was tested under two burning conditions—flaming and smoldering.

Researchers analyzed the emissions and condensed the PM into liquid form called condensate. They then used the condensate in two tests – one to evaluate potential toxic effects in the lungs of mice and the other to determine if the condensate caused DNA mutations in salmonella bacteria, a precursor to cancer.

“The health effects of the synthetic materials varied depending on the fuel type and the combustion temperatures (flaming versus smoldering), with the plastic burning in flaming conditions being the most toxic condition,” Kim says.

Specifically, smoke from flaming combustion of plastic caused more inflammation and lung injury and was more mutagenic than other samples. The burning plastic waste also generated 20 times higher PM than other burned materials under flaming conditions. The research has been published in the journal Particle and Fibre Toxicology.

“This study was a proof of concept for burning synthetic burning materials (in the combustion furnace),” says Ian Gilmour, a senior scientist on the study and co-author. “We also want to look at inhalation effects from PM and gases (from smoke) and study their relevant contributions to health effects and, second, look at the health effects from combusting other materials such as roofing tiles, lead paint, and other materials found in buildings.”

More recently, researchers performed a computational modeling analysis to determine links between chemical components in the smoke and toxicity outcomes to identify specific chemicals for their hazardous effects. This data-driven bioinformatic approach can be used to prioritize potential toxic chemicals within complex smoke mixtures. The research is published in the Nov. 14, 2022 issue of Chemical Research in Toxicology.

The wildfire smoke toxicity research will provide more information on the health effects from urban wildfire smoke. Identifying materials and combustion conditions that produce the most toxic compounds will provide valuable safety information for people who may be exposed to these types of smoke. The findings also provide important health data that can support health risk assessments in the future.

Related Science Matters Newsletter Articles:

Advancing Technology to Study the Toxicity of Wildfire Smoke