Superfund's 40th Anniversary - A Look-Back at the Decades

Go back in time with us, starting with the 1970’s to learn about the turning points and the defining moments that led to the evolution of the Superfund Program. Although all aspects of the program evolved over the years we have selected one key turning point for each decade.

On this page:

- The 1970’s: Environmental Awakening

- The 1980’s: A New Law and Program

- The 1990’s – Community Involvement: Communities as Partners

- The 2000’s – Emergencies and Focus on Response Preparedness

- The 2010’s – Innovation

- Superfund Today And Beyond

The 1970’s: Environmental Awakening

The 1970’s were an exciting time for the passage of important environmental laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. But as the “environment decade” came to a close, there was still no law addressing hazardous waste sites.

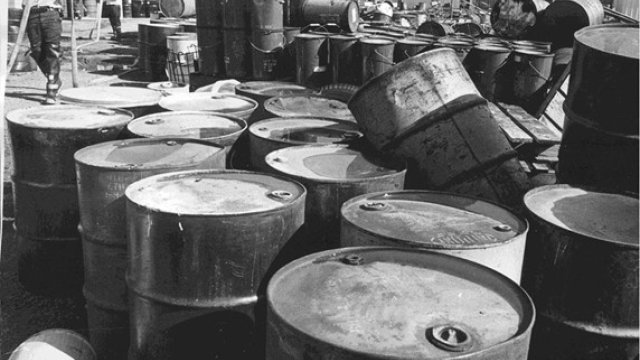

Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York, was the first hazardous waste site to gain national notoriety. Newspapers and television chronicled the fear and anger as citizens learned that 22,000 tons of dangerous chemical wastes buried 30 years earlier had begun to seep into backyards and basements.

“Quite simply, Love Canal is one of the most appalling environmental tragedies in American history. But that’s not the most disturbing fact. What is worse is that it cannot be reg

A series of emergency orders evacuating homes captured the nation’s attention and raised public awareness across the U.S. about the imminent perils of unregulated hazardous waste dumping in communities.

Abandoned hazardous waste sites across the country emerged as threats to human health and the environment, including Valley of the Drums in Kentucky, Times Beach in Missouri, and Stringfellow Acid Pits in California.

The 1980’s: A New Law and Program

“… the sheer pervasiveness of hazardous waste contamination. Even the experts didn't anticipate a problem of such magnitude as we are now addressing under Superfund and RCRA. There was only an inkling of that 20 years ago. The evidence for a major threat to public health emerged within the 15-year lifetime of EPA. And only during the last five years did we begin to appreciate the immensity of the cleanup task ahead of us.”

But public perception about the dangers at Love Canal served as a catalyst for elected officials to write the first federal legislation called Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), or Superfund, that authorized:

- the Superfund cleanup program directed by EPA.

- effective enforcement to hold waste contributors accountable for remediating sites, thus deferring further indiscriminate disposal of hazardous wastes. CERCLA also creates a Trust Fund (or 'Superfund') to finance emergency responses and cleanups.

EPA:

- built up its own response work force, with On-Scene Coordinators and Remedial Project Managers and the technical and contracting staff to support them.

- addressed urgent situations, conducting over 2,000 removal actions.

- added 1,000 sites to the National Priorities List (NPL), recovering over $1 Billion from Potentially Responsible Parties.

In 1986, Congress improved on the new law with the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) which amended CERCLA and increased the size of the fund, improved public participation, added federal facilities, and added new settlement provisions.

The 1990’s – Community Involvement: Communities As Partners

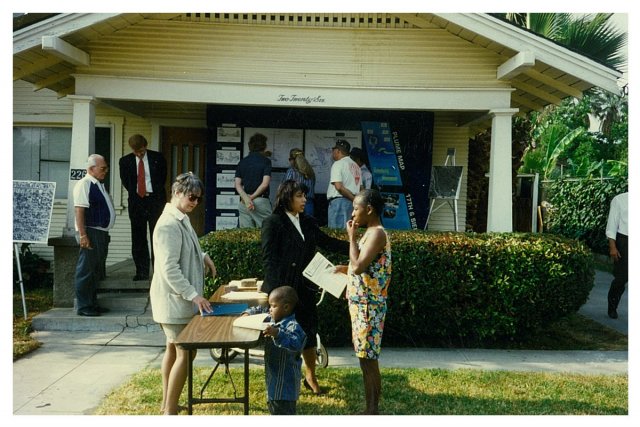

The expansion of the Superfund Community Involvement Coordinator position brought new emphasis to the important role that communities have in the decision-making process. The passage of SARA in 1986 expanded EPA’s ability and resources to engage communities in meaningful ways.

EPA became experts at involving affected communities, communicating risks, and building staff capacity by developing specialized tools and training for effectively involving citizens in the Superfund process.

Technical assistance resources through grants and contract vehicles were created to provided citizens with access to technical experts that could help them understand the complex science and risks at Superfund sites and provide input into EPA’s work.

The birth of the Environmental Justice movement in the 1980s also influenced how EPA engaged with communities, expanding our ability to ensure that all communities, regardless of race, color, national origin or income had the tools and resources they needed to participate in the Superfund process.

In the late 1990’s, an economist in EPA’s Superfund program was alerted to the fact that a grocery store built on a former Superfund site was transforming the local economy. A few other examples of redevelopment at cleaned-up sites reaping economic benefits for communities also sparked interest.

A team of employees gathered to identify how EPA could do more than clean up sites –to return the land to the communities for their use.

In 1999, the Superfund Redevelopment program was born. This national program provides communities with the tools and information needed to turn cleaned-up Superfund sites into productive assets like office parks, playing fields, wetlands, and residential areas for the community.

The 2000’s: Emergencies and Focus on Response Preparedness

This decade challenged the capabilities of the Superfund response program at every level. This decade came in like a lion and went out like a lion.

- It began with counterterrorism response for September 11, 2001, and the anthrax releases in 2001.

- It continued with the Columbia shuttle response in 2003. EPA mobilized a large federal work force using its Response Support Corps to address 4 large incidents, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, closing out the decade with the BP and Enbridge Pipeline oil spills.

- All the while, OSCs continued work on removal actions, conducting around 4,000 removal actions and RPMs continued their work on over 1,500 NPL sites.

EPA got better at dealing with these emergencies, building on its expertise

-

On-Scene Coordinator in the field after Hurricane Katrina.

-

Katrina, after the water receded.

-

Air monitoring after 9/11 attacks

-

EPA leads cleanup of anthrax contamination in D.C. office building.

The 2010’s: Innovation

In 1980, when the Superfund program was established, the practice of waste site clean-up was brand new. EPA was basically starting from scratch.

Assessing contamination in soil, under the ground, in groundwater, in surface water, and in sediments and then cleaning it up on a large scale -- created an immense and complex challenge for our scientists and engineers. The tools available were limited and often adopted from other fields, even oil exploration and extraction.

In the early days, EPA relied extensively on invasive sampling procedures and off-site laboratory capabilities to assess contamination. EPA was limited to digging up the contamination and disposing of it in hazardous waste landfills, burning it, or using cement to solidify and immobilize contaminants to store on site. We relied heavily on pumping large volumes of water from the subsurface and treating the contamination above ground.

As the program developed, a spirit of innovation emerged.

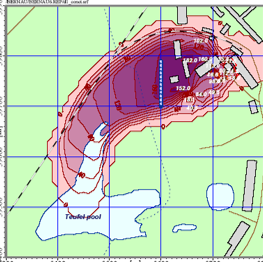

Now EPA relies on much more efficient and higher resolution tools to assess contamination and sample...

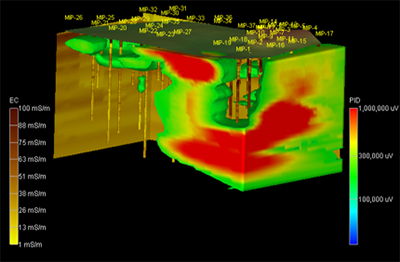

- new rapid sampling and field analytical tools, such as direct push probes, field test kits, and field portable instruments, such as x-ray fluorescence (XRF) – to more support decisions, reduce costs, and more accurately locate contaminants.

- new ways to see what is happening to contaminants in the complex geological world.

- Sensors on probes can provide data on contamination and geologic conditions below ground.

- Geophysical tools provide a noninvasive approach to give a preliminary understanding much the way an x-ray or CT scan can aid medical professionals.

- Advanced 3D visualization tools portray large quantities of data and communicate our findings.

Mapping Has Come a Long Way

And more evolved tools for cleanup. At a much greater percentage of our sites, EPA does not have to dig up the soil.

- Techniques to treat contamination in place (in situ) and apply technologies that can either destroy or remove difficult and complex contaminants.

Superfund will always continue to strive to innovate. Pressing challenges such as large mining and sediments sites or emerging contaminants will require continued improvement in the options available for cleanup.

Superfund Today And Beyond

EPA is building on improvements made through the decades to clean up the nation’s most contaminated sites, improve public health and the environment and revitalize communities.

EPA’s Superfund Task Force, commissioned on May 22, 2017, brought together EPA’s career staff and leaders to work together to review the program and implement process improvements to more efficiently and effectively remediate Superfund sites and accelerate the path to redevelopment and safe, productive reuse.

One tool developed from the recommendations of the Superfund Task Force was the Administrator’s Emphasis List. During the past three years, the Administrator’s Emphasis List has proven to be an effective tool for promoting more timely and effective cleanups. Since its creation in 2017, 20 sites have been removed from the list after achieving critical milestones that furthered site cleanup or solved issues slowing the pace of progress at a site.

The Task Force's work also enhances how we involve communities and adopt best-suited technology and innovations. EPA is now tracking progress and identifying and implementing new opportunities and approaches.

As it always has, EPA will continue to evolve and strive for new ways to better protect the health and improve the well-being of communities living near Superfund sites.

Use the slider to see before and after images of sites