TRI in the Classroom: Understanding Chemical Releases

Making everyday products like smart phones, food, and clothing can use or create toxic chemicals. The facilities that make these products must report how much of each chemical is released into the environment. They report this information to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), and anyone can look it up online. You can use the TRI to learn how and where facilities use toxic chemicals, manage toxic chemical waste, and how much waste is released into the air, water, and land.

Important Concepts

- A "release" is the way that toxic chemicals enter the air, water, and land.

- Releases happen in many ways. Some ways include spilling, leaking, pouring, dumping, or disposing into the environment.

- The TRI Program uses the terms "release, " "emission," and "discharge" to mean the same thing.

- A “facility” is a place where chemicals are used to make products or other chemicals. Examples include a power plant that makes electricity or a factory that makes tires.

- “Permits” tell a facility how much of a chemical it may release. There are permitting programs at the local, state, and federal government level.

- Some facilities that use a toxic chemical may send it to another facility “off-site” to be managed when they are done with it.

Types of Releases

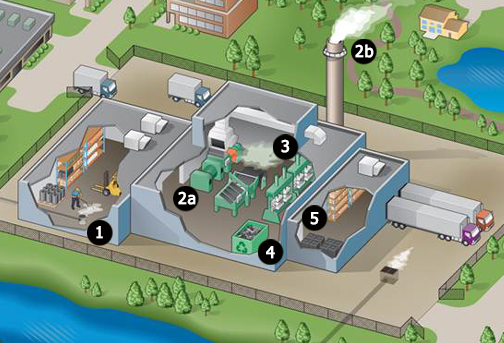

To find out about sources of chemicals at a typical TRI facility, see the Look Inside a TRI Facility webpage.

TRI tracks chemical releases at facilities across the U.S. These releases can come from “point” and “non-point” sources. A point source is a single, identifiable spot. An example of a point source is a factory smokestack (chimney) or the end of a pipe.

Non-point source pollution comes from a broader area or from multiple spots that are spread out. An example of non-point source pollution is chemicals on a field that get washed into a stream when it rains.

Facilities use special equipment that can stop some amount of chemicals from going into the environment. This equipment doesn’t stop all the chemicals, though. Some amount of the chemicals can leave the facility and go into the air, water, or land.

Most releases that facilities report to TRI are intentional and happen when the facility is operating normally. Facilities must always follow the rules of their permits when releasing chemicals into the environment. .

On-Site Releases

On-site releases happen on the facility’s property. Facilities must tell EPA how much of each chemical went into the air, into surface water, or into the land each year. Facilities use the categories below to report that information. For some categories, like land disposal, there are also subcategories for facilities to provide more details about how the chemicals were released.

| Air | Surface Water | Land (Disposal) |

|---|---|---|

Stack or point air emissions: Releases into the air through a single, identifiable spot like a stack, duct, or pipe. Fugitive or non-point air emissions: Releases into the air that do not go through a smokestack, duct, or pipe. Examples are chemicals entering the air through equipment leaks, a building’s ventilation system, or evaporation from a pond that holds liquid waste containing chemicals. |

Discharges to receiving streams or water bodies: Releases into streams, ponds, lakes, rivers, oceans, or other bodies of water. These releases can come from a single, identifiable spot, like a pipe that goes into a river. Releases can also come from a larger area, such as rainwater flowing over equipment and then into a nearby stream. Facilities must also report the names of each water body that chemicals are released into. |

There are multiple types of land disposal. Underground injection wells: Places where liquid waste that contains chemicals is disposed underground and stored in rock formations. Landfills: Sites that are built and managed to hold many types of solid and liquid waste. Surface impoundments: Uncovered ponds or lagoons used to store liquid waste temporarily. Land treatment/ application farming: Putting liquid or solid waste on top of soil or mixing it into the soil. |

Off-Site Releases (Off-Site Transfers for Disposal)

Some facilities send waste containing chemicals to other facilities that are better able to handle it. What these other facilities do with the chemicals varies. Some are landfills, some are wastewater treatment plants, and others burn waste. On their TRI reporting forms, facilities report where they sent the waste, how much of each chemical was in the waste, and what happened to the waste at the other location. Chemical waste that is disposed of at the other facility is reported to TRI as an “off-site release” or an “off-site transfer for disposal.”

For example, a facility might report that it sent 100 pounds of mercury to Acme Waste Management at 123 Main Street in Roswell, New Mexico, for disposal in an underground injection well. Even though the chemical has now been sent to another facility, the chemical will still be counted as part of the original facility’s total TRI releases for that year.

To learn about the other ways that facilities manage waste containing chemicals, see TRI in the Classroom: Understanding Chemical Waste Management.

Determining Release Quantities

Facilities must estimate the amount of chemicals they release into the air, land, or water each year for TRI reporting. They often do this using equations or information about how the chemicals were handled at the facility. EPA provides a TRI reporting form that facilities use to report their estimates.

Some facilities are required to directly measure the chemicals they release because of laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. For example, a facility must measure how much mercury it puts into the water to make sure it is following the rules of its Clean Water Act permit.

If facilities have exact measurements of the chemicals they released, they should use these for TRI reporting instead of estimates.