Water Reuse Case Study: Fairfax County, Virginia

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and partners have created a series of case studies that highlight the different water reuse approaches communities have taken to meet their water quality and water quantity needs. Each case study contains information about the technical, financial, institutional, and policy aspects of these water reuse systems and the communities in which they are located.

On this page:

- Overview

- Context

- Solution

- Policy, Institutional, and Regulatory Environment

- Financial and Contractual Agreements

- Benefits

- Lessons Learned and Conclusions

- Background Documents

Location: Fairfax County, Virginia

Treatment Capacity: Up to 6.6 million gallons (24.9 million liters) per day, average 3 million gallons per day

Status: Operational since 2012

Overall Cost: $16,000,000

Source of Water: Treated municipal wastewater

Reuse Application: Non-potable uses such as landscape and ball field irrigation, industrial uses such as cooling water

Benefits: Offsetting potable water demands, addressing nutrient loading and permit compliance; TMDL mitigation

Overview

Fairfax County reuses its treated municipal wastewater for centralized non-potable applications (such as commercial car washing, construction, and street cleaning). Key reasons for pursuing reuse included: to treat wastewater for a growing population without costly upgrades to its municipal wastewater treatment plant, to reduce nutrient discharges to the Chesapeake Bay; to meet TMDL requirements, and to lower the demand on potable water supplies by using reclaimed water for non-potable uses.

Related Links

Context

Fairfax County’s Wastewater Management Program consists of sewage collection, treatment, and residual waste facilities for commercial users and more than 268,000 residents. The county’s Department of Public Works and Environmental Services manages the wastewater program, including the Noman M. Cole, Jr., Water Pollution Control Plant (NMCPCP). The NMCPCP treats an average of 50 million gallons (189 million liters) of wastewater per day and discharges into the Pohick River, a tributary in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The need for waste management in the county is expected to grow as the local population and commercial activities increase.

Due to excess nutrients in the watershed, the Chesapeake Bay is an impaired waterbody, despite restoration efforts that have taken place for more than 30 years. The excess nutrients cause seasonal hypoxia zones, or areas without oxygen, in the Bay, which makes these zones inhospitable to fish and other aquatic wildlife. In response, the EPA set strict Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) requirements to reduce phosphorus, nitrogen, and sediment discharges throughout its 64,000-square-mile (166,000-square-kilometer) watershed that includes portions of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. A TMDL is a “pollution diet” that identifies the maximum amount of a pollutant a waterway can receive and still meet applicable water quality standards under the Clean Water Act. The discharge of nutrients and other contaminants into the Chesapeake Bay watershed is also an issue because surface waters in the area are potable water sources for water treatment plants in the region.

As a step in the continued restoration process and to help further reduce nutrient loading to the Chesapeake Bay, the State of Virginia assigned TMDL limits to the NMCPCP. The NMCPCP therefore provides an extremely advanced level of treatment and has continuously met these strict nutrient discharge requirements. However, the nutrient loading requirements of the Chesapeake Bay TMDL will become more stringent, partially enabled by improved treatment technologies. Therefore, the county must look for other ways to reduce nutrient discharges to the Bay. The Chesapeake Bay TMDL and the associated nutrient discharge limits have been drivers for water reuse across the various wastewater plants that discharge to the Bay.

As responsible water stewards, the county’s Wastewater Management Leadership Team focused on long-range planning, strategy, continuous improvement, wastewater capacity issues, and financial management to evaluate options for reducing nutrient discharges. In addition to meeting nutrient TMDLs, other key drivers for pursuing reuse included avoiding upgrades needed to treat the wastewater of a growing county, the cost savings from using recycled water to offset potable water use, and industry-wide support for the adoption of water reuse. The key challenges the county faced included identifying local entities who could commit to long-term reclaimed water use and the costs associated with constructing a pumping station and new pipelines to deliver reclaimed water to each user. To be feasible, the county needed to design the project to achieve a 20-year payback period.

Solution

Identifying Potential Uses and Users

To pursue water reuse, Fairfax County needed to identify potential end-users who could enter a contract to receive the county’s reclaimed water; they did this by searching water records and potential land application sites. Selection of local users lowers the cost of pumping and distributing the reclaimed water. The county’s search revealed several types of potential users and uses, including:

- Cooling tower water for the Covanta Fairfax, Inc., Energy Resource Recovery Facility (E/RRF).

- Spray irrigation for the Laurel Hill Golf Course and the South County Ball Fields.

- Other activities, such as car washing, bulk filling for construction, landscaping, and street cleaning.

Each of these end uses needs high quality water in compliance with Virginia’s restrictions on water reuse. In addition to modest treatment upgrades, the county needed to build an adequate pumping station and pipelines to transport the reclaimed water to the end users. The county did not consider including potable reuse in this project because the source water for most of the county’s potable water treatment facilities is far upstream of the NMCPCP.

Covanta Fairfax E/RRF was a critical partner for the success of the reclaimed water project. Prior to an agreement with the county, the Covanta facility used over 3 million gallons (11 million liters) per day of potable water for evaporative cooling to convert trash to steam for energy generation. This facility was just 7 miles (11 kilometers) from the county’s wastewater treatment plant. Water in the facility’s cooling towers evaporates and must be replenished daily. During the annual blowdown process, the used water is discharged back to the county’s treatment plant.

To reach an agreement with Covanta, multiple meetings were required for this potential user, including contract development and cost negotiations with both regional and national authorized representatives of Covanta, since the agreement required an extended time commitment and land for the county’s new water storage tank and valves.

After switching to reuse water, Covanta reduced its dependence on potable water and reduced its operating costs while supporting its business in reaching its sustainability goals. Currently, the county provides about 592 million gallons (2.2 billion liters) per year of recycled water to the facility, most of which is lost during the steam generation process.

Communicating with Customers and the Public about the Benefits of Reclaimed Water

In addition to feasibility planning, the county held meetings with the reclaimed water customers to educate them about the benefits of water reuse for their facilities. One of the reclaimed water customers, the South County Ball Fields are owned by another branch of the county and were very supportive of the reuse concept and the reduced maintenance it would bring to the ball fields. The Laurel Hill Golf Course owners were also very supportive and worked with the county to determine the best route for the pipeline to reach their facility.

To prepare the nearby communities for construction of a pipeline needed to transport reclaimed water, the county conducted multiple outreach meetings with homeowners’ associations. The county also developed a brochure to inform the public of the project, educate them about the benefits of using reclaimed water, and—most importantly—how the quality of the reclaimed water compares to natural waters in their community.

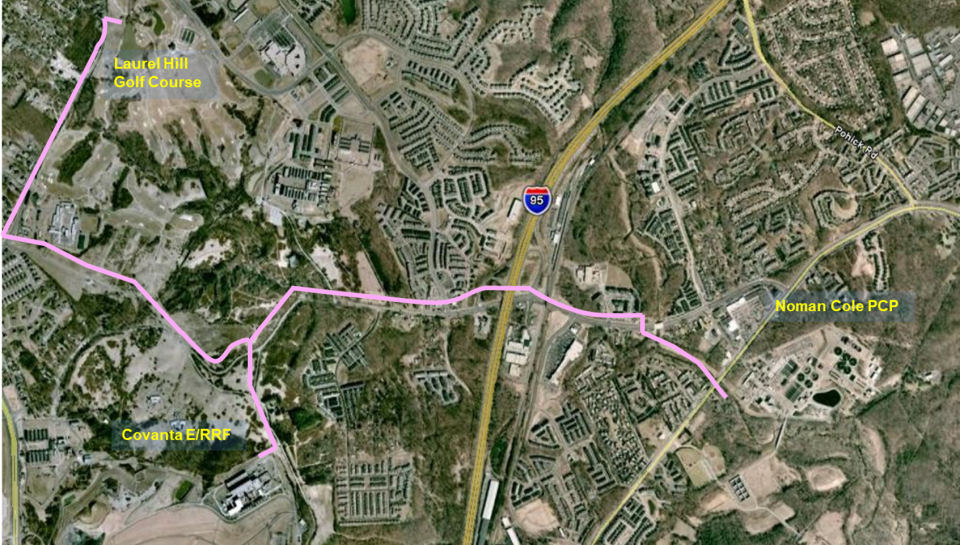

Public presentations engaged a variety of other stakeholders in addition to the general public, such as the county’s drinking water utility (which would lose revenue due to the project), the county board, and various local citizen groups. Each of the presentations involved a discussion of the environmental sensitivity of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries to nitrogen and phosphorus and the ways in which the project could benefit the health of the bay by reducing nutrient loading. The presentations also communicated how the new recycled water source project would reduce overall costs and meet the needs of the region’s growing population. The public presentations were well-received, overall, and the project progressed. Figure 1 depicts the major recycled water pipeline route to the users.

Treatment and Pumping Requirements

The Noman M. Cole, Jr., Water Pollution Control Plant (NMCPCP) is a highly advanced treatment facility and only needed small modifications to produce water of sufficient quality for reuse. Specifically, the treated effluent from the NMCPCP is considered “Level 1” reuse water, only needing pipeline disinfection prior to distribution for non-potable uses. Table 1 lists the critical limits and annual averages for the NMCPCP based on a maximum recycled water discharge flow of 6.6 million gallons (25 million liters) per day.

|

Parameter |

Annual Average (2021) |

Reuse Limits Level 1 |

|---|---|---|

|

Five-day carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand |

Less than 2.0 mg/L |

8 mg/L |

|

pH |

7.3 |

6.0–9.0 |

|

Turbidity |

0.75 NTU |

5 NTU |

|

Total suspended solids |

0.86 mg/L |

Secondary treatment with filtration |

|

Total residual chlorine (30 minutes) |

1.1 mg/L |

1 mg/L |

|

Total phosphorus |

0.8 mg/L |

1 mg/L |

|

Total nitrogen |

2.6 mg/L |

8 mg/L |

|

E. coli (monthly geometric mean) |

1 colonies/100 mL |

24/100 mL |

Abbreviations: milligrams per liter (mg/L), milliliters (mL), nephelometric turbidity units (NTU).

Fairfax County retrofit the NMCPCP treatment system to include a sodium hypochlorite feed used to disinfect the reclaimed water and meet Virginia reuse regulations. Existing chlorination tanks were used to add enough sodium hypochlorite to the reclaimed water to keep the distribution lines clean. The state required additional chlorine contact time, which was achieved by keeping the reclaimed water in the effluent pipeline for more than the 30 minutes.

In addition to disinfection treatment retrofits, the reuse project required new pump stations, storage tanks and pipe networks to transport water from the treatment plant to the users. Specifically, the NMCPCP added three new pumps and a 1-million-gallon (3.8-million-liter) elevated water tank to keep the water pressure high in the distribution lines. The use of the elevated water tank was innovative because it avoided the need to add larger pumps to the system which would have added to the project’s cost. The storage tank and pumping systems supplied enough pressure for the reclaimed water to reach users through the new 57,000 foot (17,000 meter) purple pipeline built specifically for the delivery of reclaimed water (Figure 2).

Policy, Institutional, and Regulatory Environment

Virginia administers the Virginia Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) as a delegated state and issues permits to dischargers. Water reuse is not mandatory in Virginia, but it is encouraged. The state has developed reuse regulations which set the requirements for recycled water purveyors to obtain a reuse permit from the state. Where applicable, reuse approaches are considered within the VPDES permitting process and the ability for a facility to distribute recycled water becomes an amendment to the facility’s VPDES permit. Virginia is proactive in seeking multiple ways to reduce nutrients to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries and includes water reuse as an approach for achieving that goal.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality issues the reuse permits based on Virginia state reuse regulations. The counties provide building permits where required. Virginia’s reuse regulations cover many types of uses for recycled water, including landscape irrigation, centralized non-potable reuse such as cooling tower water and car washes, and also indirect potable reuse. The regulations identify the requirements for the various types of reuses (Level 1 and 2) and set limits and “corrective action levels” that, when reached, mean the owner must follow a corrective action plan.

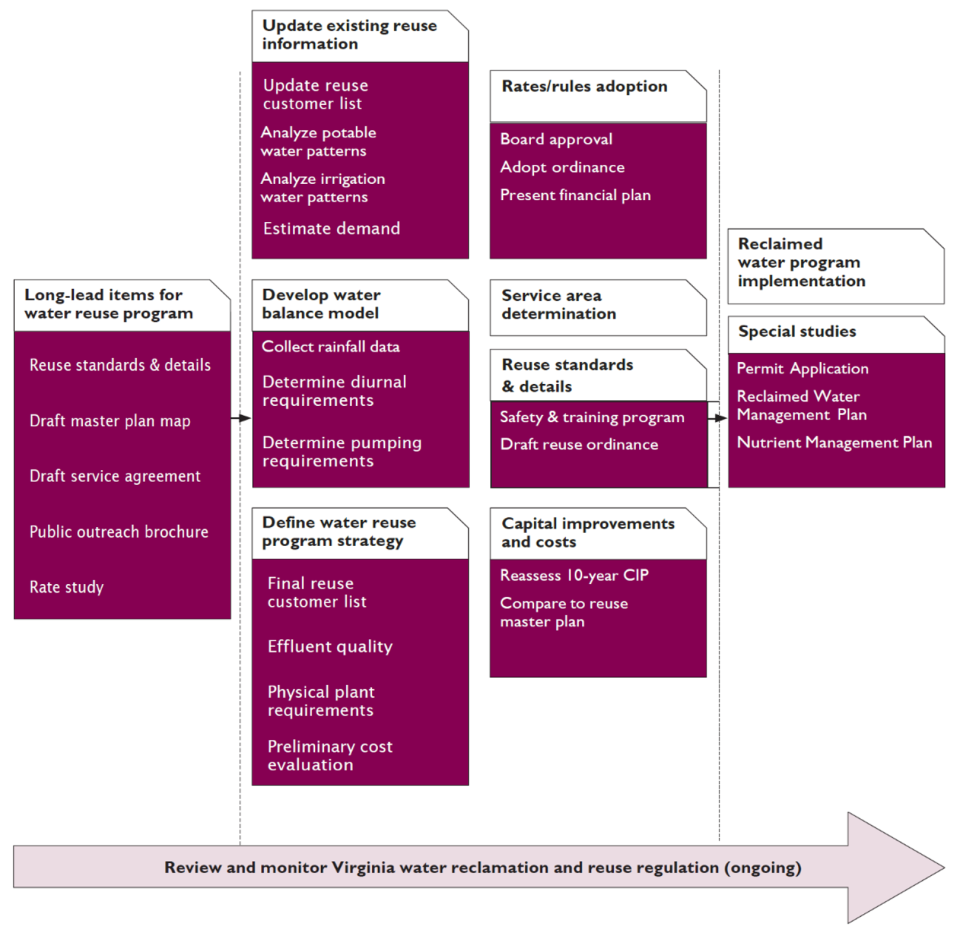

Based on the reuse regulation requirements, Fairfax County began developing its own program to reclaim wastewater for beneficial reuse. Initial discussions, regulatory guidance, and permitting needs helped the county identify several key elements for an effective program. Figure 3 illustrates the main workflow process and key elements included in the development of the County’s reuse program.

Financial and Contractual Agreements

Financial

Long-Term Planning

Fairfax County performed financial analyses to support a sustainable 20-year plan and determine payback periods on its investment in reuse infrastructure. This analysis involved determining the annual funds needed for overall capital improvement and operations, including debt service and debt coverage. Through this process, the county determined an estimated cost per 1,000 gallons (3,800 liters) of recycled water that the Noman M. Cole, Jr., Water Pollution Control Plant (NMCPCP) could produce. This estimate included the pump system at the plant, the hypochlorite system, pump controls, water tank, pipeline and distribution or connection costs, energy costs, replacement costs, operations and maintenance, and personnel costs associated with the operation of the reuse facility. The county used these calculations to determine the user fees required to fund the reuse system. Ultimately, the fee per gallon of recycled water was a calculation for bulk users and point users. Federal funds were available to help offset some project costs (discussed further below), and the user fee accounted for nearly half the cost of the supplied reuse water. Overall, the county has met its 20-year return on investment goal and now uses the revenue to supplement the treatment facility’s annual budget.

Additional Users

In addition to Covanta Fairfax E/RRF, three other users agreed to sign contracts with the county to irrigate golf courses, landscaping, and local football fields. Although these other facilities needed much less water than the E/RRF, the pipeline that served the E/RRF could also provide access to these other users’ locations and reduce the E/RRF’s costs. Presently, the county treats an average of 40 million gallons (151 million liters) per day at the NMCPCP and delivers more than 3 million gallons (11 million liters) reclaimed water per day to these four facilities.

Federal Funding Assistance

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) began matching funds for infrastructure improvements that specifically targeted reducing nutrient discharges to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. ARRA included projects that could be ready for construction by September 2012. For the county to receive the matching funds, it decided to construct its water reuse facilities using a design-build method so that construction could get started within six months and before the ARRA construction deadline. ARRA reduced the cost of the design and engineering fees by about half (or up to $8,000,000).

The ARRA funding was a critical factor in reducing the overall life cycle cost in dollars per 1,000 gallons (3,800 liters). Ultimately, the fee established for recycled water was nearly half that of potable water and provided a new source of revenue for the treatment plant’s enterprise fund. The ARRA funding covered 50 percent of the total capital costs (about $16 million). The county paid the remaining balance of the capital cost through bonding.

Nutrient Credit Trading

The county also participates in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Nutrient Credit Exchange Program. Under this program, other Virginia utilities in the bay watershed and its tidal tributaries may enter agreements to purchase credits for nitrogen and phosphorus discharge. This program helps utilities that cannot feasibly reduce their nitrogen and phosphorus discharges through other means to meet stringent limits. Fairfax County has credits available for purchase under the program and receives small revenues from those credits.

Contractual

The Virginia water reclamation and reuse regulations require that appropriate contractual agreements be developed and approved to secure the project’s longevity. The county hired a consultant to develop a recycled water user contract that includes the costs per gallon of the reuse water per 1,000 gallons (3,800 liters). This cost was based on the capital and operations cost of the program for a 20-year payback period. Two types of contract agreements were developed for the county:

- A general user agreement for major users with offsite connections.

- A “bulk fill” agreement for users that need ad hoc truck filling for landscaping, street cleaning, and other periodic uses.

The first contractual agreement developed was with the user Covanta Fairfax, which owns and operates the E/RRF and receives recycled water from the county. After three months of negotiations, Covanta agreed to use up to 3 million gallons (11 million liters) a day of recycled water for blowdown, cleaning, and makeup water. The county built a pipeline, water storage tank, backflow prevention valve, and second connection to Covanta’s current potable process water line. The contract between the county and Covanta contains a time limit of 20 years, minimum flow requirements, water quality requirements, and other commitments.

The timeline for design, construction, program development, and permitting were driven by the short timelines set for ARRA funding. A preliminary engineering report was generated within two months and the county was able to issue a design-build request for proposal to construct components of the reuse system. The construction took a little over two years due to the need for seven separate permits to cross major roads and a major interstate highways.

Benefits

Conserves valuable drinking water: The project allows Fairfax County to reclaim over 3 million gallons (11 million liters) of water each day, which greatly reduces the amount of water needed from the Potomac River. The county has set an example for other resource recovery facilities to look for long-term solutions for water stewardship and water supply sustainability.

Provides additional revenue income: The county currently provides recycled water to the Covanta Fairfax E/RRF, the Laurel Hill Golf Course, and the South County Public School ball fields. Most of this water is consumptive. It can earn up to $279,000 per year from recycled water sales and over $17,800 in nutrient exchange credits to offset the costs of its water reuse program.

Conserves capacity: By creating its water reuse program and facility, the county has been able to meet drinking water needs of the community, even as it continues to grow.

Reduces nitrogen and phosphorus discharges to the Chesapeake Bay: Each gallon of treated municipal wastewater diverted for water reuse reduces the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus discharged to Pohick River, a tributary to the bay. This helps the county meet permit limits for nutrient discharges and helps keep the receiving stream healthy for the many citizens who enjoy its use.

Water reuse promotion and demonstration: The success of the county’s water reuse program has set a high standard for other municipalities and has helped encourage others to develop their own programs. The water reuse program has been well-received by the public. The program was and is intended to be perpetual and has become an integral part of the county’s services to its ratepayers by providing a cheaper alternative to potable water use for some applications and by generating revenues that help offset treatment costs.

Lessons Learned and Conclusions

One of the major factors in the success of implementing the water reuse program was the dedication of the county and its residents to making water conservation and stewardship a high priority. Educational meetings with multiple citizen’s groups resulted in a high level of support for the program. In addition, the county’s willingness to plan on a longer time horizon and consider water reuse as a way to reduce nutrient discharges to the Chesapeake Bay was critical. ARRA funding was another major contributor to the success of the program, as it helped accelerate its development and implementation.

In developing the water reuse program and putting it into action, Fairfax County learned the following lessons:

- Develop and adhere to a good “road map” to keep a project from getting out of control.

- Engage the ratepayers early and often to get their understanding and support.

- If the recycled water provider is not the same entity as the potable water provider, engage and educate both parties early. Their goals may seem to be at odds at first, but reduced demand on potable water supplies may prevent the potable water provider from having to construct new reservoirs or other infrastructure. To see the mutual benefit of water reuse, drinking water and wastewater utilities will need to collaborate using a “one water” planning framework to help improve resilience and sustainability in the local community.

- Periodically revisit lifecycle cost calculations to account for changes in costs over time. Revisions could take place during a capital improvement plan cycle.

- Consider the costs associated with operating the equipment, personnel required for monitoring, and maintenance costs for the life cycle of the system.

The Fairfax County water reuse program is approved to produce up to 6.6 million gallons (25 million liters) per day of Level 1 reclaimed water for reuse. This provides room for increased reclaimed water use as the county engages new users and as the county grows. The county’s partnership with other major users similar to Covanta Fairfax could lead to expansion of that company’s use of recycled water; the partnership has set a positive precedent for facilities interested in water conservation and good stewardship.

Background Documents

- CDM. 2010. Fairfax County Wastewater Management Reclaimed Water Management Plan.

- Fairfax County. 2022. Fairfax County Sewer System Certification Report.

- Water Reclamation and Reuse Regulation, 9 Va. Admin. Code § 25-740.