Progress Report - Air Quality

Air Quality

On this page:

Last updated on February 28, 2024

Data current through 2022

Sulfur Dioxide

Sulfur oxides are a group of highly reactive gases that can travel long distances in the upper atmosphere and predominantly exist as sulfur dioxide (SO2). The primary source of SO2 emissions is fossil fuel combustion at power plants. Smaller sources of SO2 emissions include industrial processes, such as extracting metal from ore, as well as the burning of high sulfur-containing fuels by locomotives, large ships, and non-road equipment. SO2 emissions contribute to the formation of fine particle pollution (PM2.5) and are linked with adverse effects on the respiratory system.1 In addition, particulate sulfate degrades visibility and, because sulfur compounds are typically acidic, can harm ecosystems when deposited.

National SO₂ Air Quality

- Based on EPA’s air trends data, the national average of SO2 annual mean ambient concentrations decreased from 12.1 parts per billion (ppb) to 0.7 ppb (94 percent) between 1980 and 2022.

- Since the first year of the Acid Rain Program (ARP), three years have seen reductions in average SO2 concentrations of greater than 20 percent: 1994–1995 (22 percent); 2008–2009 (21 percent); and 2014–2015 (23 percent).

Nitrogen Oxides

Nitrogen oxides are a group of highly reactive gases including nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). In addition to contributing to the formation of ground-level ozone and PM2.5, NOX emissions are linked with adverse effects on the respiratory system.3, 4 NOX also reacts in the atmosphere to form nitric acid (HNO₃) and particulate ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3). HNO3 and nitrate (NO3), reported as total nitrate, can also lead to adverse health effects and, when deposited, cause damage to sensitive ecosystems.

Although the ARP and CSAPR programs have significantly reduced NOX emissions from power plants and improved air quality, emissions from other sources (such as motor vehicles and agriculture) contribute to total nitrate concentrations in many areas. Ambient nitrate levels can also be affected by emissions transported via air currents over wide regions.

Regional Changes in Air Quality

- Regional average ambient SO2 concentrations declined in the eastern U.S. by 95 percent from the 1989–1991 observation period to the 2020–2022 observation period.

- Average ambient particulate sulfate concentrations have decreased by 51 to 84 percent in observed regions from 1989–1991 to 2020–2022.

- Average annual ambient total nitrate concentrations declined 61 percent from 1989–1991 to 2020–2022 in the eastern U.S., with the most significant decreases occurring after 2002, coinciding with the implementation of the NOX Budget Trading Program, followed by Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR), Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR), and CSAPR Update.

| Measurement | Region | Annual Average, 2000–2002 | Annual Average, 2020–2022 | Percent Change | Number of Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambient Particulate Sulfate Concentration (µg/m³) | Mid-Atlantic | 4.8 | 1 | -79 | 13 |

| Midwest | 4.3 | 1 | -77 | 16 | |

| North Central | 1.3 | 0.6 | -54 | 2 | |

| Northeast | 2.6 | 0.6 | -77 | 6 | |

| Pacific | 0.8 | 0.5 | -38 | 5 | |

| Rocky Mountain | 0.7 | 0.4 | -47 | 10 | |

| South Central | 2.9 | 1.2 | -59 | 2 | |

| Southeast | 4.2 | 1 | -76 | 12 | |

| Ambient Sulfur Dioxide Concentration (µg/m³) | Mid-Atlantic | 8 | 0 | -100 | 13 |

| Midwest | 6.8 | 0.6 | -91 | 16 | |

| North Central | 1 | 0.4 | -60 | 2 | |

| Northeast | 3.4 | 0.3 | -91 | 6 | |

| Pacific | 0.4 | 0.2 | -35 | 5 | |

| Rocky Mountain | 0.5 | 0.2 | -60 | 10 | |

| South Central | 1.1 | 0.4 | -64 | 2 | |

| Southeast | 3.4 | 0.3 | -91 | 12 | |

| Ambient Total Nitrate Concentration (µg/m³) | Mid-Atlantic | 3 | 1.2 | -60 | 13 |

| Midwest | 4.1 | 1.8 | -56 | 16 | |

| North Central | 1.2 | 0.7 | -42 | 2 | |

| Northeast | 1.9 | 0.8 | -58 | 6 | |

| Pacific | 1.8 | 0.9 | -50 | 5 | |

| Rocky Mountain | 0.8 | 0.5 | -38 | 10 | |

| South Central | 1.5 | 0.9 | -40 | 2 | |

| Southeast | 2.3 | 0.9 | -61 | 12 |

Notes:

• Averages are the arithmetic mean of all sites in a region that were present and met the completeness criteria in both averaging periods. Thus, average concentrations for 2000 to 2002 may differ from past reports.

• Data are from CASTNET monitoring sites which are typically located away from stationary emissions sources. Percent change is calculated from the base period of 2000–2002 to coincide with the deposition changes in the Acid Deposition section of the Progress Report.

• Bolded numbers indicate a statistically significant percent change. Statistical significance was determined at the 95 percent confidence level (p < 0.05) using a Student’s t-test. Because changes that are not statistically significant may be unduly influenced by measurements having large variability or insufficient data completeness, regional results must include at least five sites to evaluate statistical significance.

Ozone

Ozone pollution – also known as smog – forms when NOX and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) react in the presence of sunlight. Major anthropogenic sources of NOX and VOC emissions include electric power plants, motor vehicles, solvents, and industrial facilities. Meteorology plays a significant role in ozone formation and hot, sunny days are most favorable for ozone production. For ozone, EPA and states typically regulate NOX emissions during the summer when sunlight intensity and temperatures are highest.

Ozone Standards

In 1979, EPA established National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for 1-hour ozone at 0.12 parts per million (ppm), or 124 parts per billion (ppb). In 1997, a more stringent 8-hour ozone standard of 0.08 ppm (84 ppb) was finalized, revising the 1979 standard. CSAPR was designed to help downwind states in the eastern U.S. achieve the 1997 ozone NAAQS. Based on extensive scientific evidence about ozone’s effects on public health and welfare, EPA strengthened the 8-hour ozone standard to 0.075 ppm (75 ppb) in 2008. Finalized in 2016, the CSAPR Update was designed to help downwind states meet and maintain the 2008 ozone NAAQS. EPA further strengthened the 8-hour NAAQS for ground-level ozone to 0.070 ppm (70 ppb) in 2015. EPA revoked the 1-hour ozone standard in 2005 and more recently revoked the 1997 8-hour ozone standard in 2015.

Regional Trends in Ozone

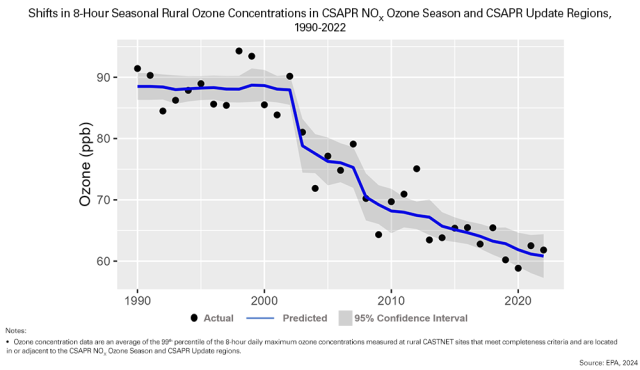

EPA investigated trends in daily maximum 8-hour ozone concentrations measured at rural Clean Air Status and Trends Network (CASTNET) monitoring sites within the states requiring ozone season reductions under CSAPR and CSAPR Update, as well as in adjacent states. Rural ozone measurements are useful in assessing the impacts on air quality resulting from regional NOX emission reductions because they are typically less affected by local sources of NOX emissions (e.g., industrial and mobile) than urban measurements. Reductions in rural ozone concentrations are largely attributed to reductions in regional NOX emissions and transported ozone.

The ARIMA model is an advanced statistical analysis tool used to visualize the trend in regional ozone concentrations following implementation of various programs geared toward reducing ozone season NOX emissions. To show the shift in the highest daily ozone levels, EPA modeled the average of the 99th percentile of the daily maximum 8-hour ozone concentrations measured at CASTNET sites (as described above).

Meteorologically–Adjusted Daily Maximum 8-Hour Ozone Concentrations

Variations in weather conditions play an important role in determining ozone concentrations. Ozone is more readily formed on warm, sunny days when the air is stagnant. Conversely, ozone production is more limited when it is cloudy, cool, rainy, or windy. EPA uses statistical models to adjust for the variability in seasonal ozone concentrations due to weather to provide a more accurate assessment of the underlying trend in ozone driven by emissions.

Meteorologically–adjusted ozone trends provide additional insight on the influence of CSAPR NOX Ozone Season program and CSAPR Update emission reductions on regional air quality. EPA retrieved daily maximum 8-hour ozone concentration data from the Air Quality System (AQS) and daily meteorology data from the National Weather Service for 378 ozone monitoring sites located in the CSAPR Update region. EPA uses these data in statistical models to account for the influence of weather on seasonal average and 98th percentile ozone concentrations at each monitoring site.1

- The average reduction in seasonal mean ozone concentrations in the CSAPR Update region from 2000–2002 to 2020–2022 was about 10 ppb (19 percent), while the average reduction in the 98th percentile concentrations was about 22 ppb (26 percent) before adjusting for weather-related effects.

- The average reduction in the meteorologically-adjusted seasonal mean ozone concentrations in the CSAPR Update region from 2000–2002 to 2020–2022 was about 11 ppb (21 percent), while the average reduction in the 98th percentile concentrations was about 22 ppb (25 percent) after adjusting for weather-related effects.2

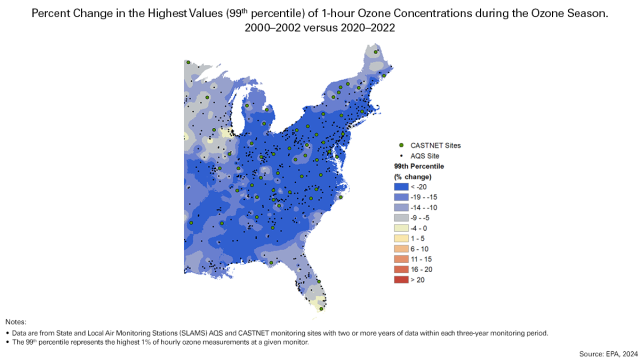

Ozone Season Changes in 1-Hour Ozone

- There was an overall regional reduction in ozone levels between 2000–2002 and 2020–2022, with a 25 percent reduction in the highest (99th percentile) ozone concentrations in CSAPR and CSAPR Update states.

- Results demonstrate how NOX emission reduction policies have benefitted 1-hour ozone concentrations in the eastern U.S. – historically, the region that the ozone policies were designed to target.

Annual Trends in Rural 8-Hour Ozone

- From 2020 to 2022, rural ozone concentrations averaged 61 ppb in CSAPR states, a decrease of 27 ppb (31 percent) from the 1990 to 2002 average period.

- The ARIMA model shows how the reductions in rural ozone concentrations correlate with the implementation of the NBP in 2003 and the CAIR NOX Ozone Season program in 2009. There was a 10 ppb reduction in ozone from 2002 to 2004 and a 6 ppb reduction in ozone from 2007 to 2009.

- This analysis using the ARIMA model is designed to correlate the observed ozone with regional reductions in emissions resulting from regulations. Annual variability in observed Ozone will also be influenced by meteorological factors, changes in climate-driven emissions sources (e.g., wildfires) or global shifts in anthropogenic emissions (e.g. 2020 stay at home orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

- Nine of the ten lowest observed annual ozone concentrations were between 2013 and 2022. Ozone season NOX emissions fell steadily under CAIR and continued to drop after implementation of CSAPR in 2015 and CSAPR Update in 2017. In addition, implementation of the mercury and air toxics standards, which began in 2015, achieves co-benefit reductions of NOX emissions.

Changes in Ozone Nonattainment Areas

The majority of ozone season NOX emission reductions in the power sector after 2003 are attributable to the NOX Budget Trading Program, the Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR), the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR), and the CSAPR Update. As power sector emissions are an important component of the NOX emission inventory, it is reasonable to conclude that the reduction in ozone season NOX emissions from these programs has significantly contributed to improvements in ozone concentrations and attainment of the ozone health-based air quality standard.

Emission reductions under these power sector programs have helped many areas in the eastern U.S. reach attainment for the 2008 ozone NAAQS. However, several areas continue to be out of attainment with the 2008 ozone NAAQS, and additional ozone season NOX emission reductions are needed to attain that standard as well as the strengthened ozone standard finalized in 2015.

In order to help downwind states and communities meet and maintain the 2008 ozone standard, EPA finalized the CSAPR Update in September 2016 to address the transport of ozone pollution that crosses state lines in the eastern U.S. Implementation began in May 2017 to further reduce ozone season NOX emissions from power plants in 22 states. Starting June 2021, further emission reductions were required under the Revised CSAPR Update at power plants in 12 of the 21 CSAPR Update states.

- Ninety-two of the 113 areas originally designated as nonattainment for the 1997 8-hour ozone NAAQS (0.08 ppm) are in the eastern U.S. and are home to about 131 million people.5 These nonattainment areas were designated in 2004 using air quality data from 2001 to 2003.6

- Based on data from 2020 to 2022, 88 of the eastern ozone nonattainment areas now show concentrations below the level of the 1997 standard, while the remaining four areas had incomplete data.

Changes in 1997 Ozone NAAQS Nonattainment Areas in CSAPR Region, 2001-2003 (Original Designations) versus 2020-2022

- Twenty-two of the 46 areas originally designated as nonattainment for the 2008 8-hour ozone NAAQS (0.075 ppm) are in the eastern U.S. and are home to about 80 million people.5 These nonattainment areas were designated in 2012 using air quality data from 2008 to 2010 or 2009 to 2011.

- Based on data from 2020–2022, 82 percent (18 areas) of the eastern ozone nonattainment areas now show concentrations below the level of the 2008 standard, while three areas have shown progress toward meeting the standard and one area has incomplete data. It is reasonable to conclude that ozone season NOX emission reductions from the NBP, CAIR, CSAPR, and CSAPR Update have significantly contributed to these improvements in ozone air quality.

Changes in 2008 Ozone NAAQS Nonattainment Areas, 2008-2010 (Original Designations) versus 2020-2022

- Twenty-two of the 52 areas originally designated as nonattainment for the 2015 8-hour ozone NAAQS (0.070 ppm) are in the eastern U.S. and are home to about 85 million people.5 These nonattainment areas were designated in 2018 using air quality data from 2014 to 2016 or 2015 to 2017.

- Based on data from 2020–2022, seven of the 22 eastern ozone nonattainment areas now show concentrations below the level of the 2015 standard, and an additional eight areas have made progress toward meeting the standard.

Changes in 2015 Ozone NAAQS Nonattainment Areas, 2015-2017 (Original Designations) versus 2020-2022

Particulate Matter

Particulate matter—also known as soot, particle pollution, or PM—is a complex mixture of extremely small particles and liquid droplets. Particle pollution is made up of several components, including nitrate, ammonium, and sulfate compounds, organic compounds, metals, and soil or dust particles. Fine particles (defined as particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5 μm, and abbreviated as PM2.5) can be directly emitted or can form when gases emitted from power plants, industrial sources, automobiles, and other sources react in the air.

Particle pollution—especially fine particles—contains microscopic solids or liquid droplets so small that they can get deep into the lungs and cause serious health problems. Numerous scientific studies have linked particle pollution exposure to a variety of problems, including the following: premature death; increased respiratory symptoms such as irritation of the airways, coughing, or difficulty breathing; decreased lung function; aggravated asthma; development of chronic bronchitis; irregular heartbeat; and nonfatal heart attacks.7, 8, 9

PM Standards

In 1997, EPA set the first standards for fine particles at 65 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), measured as the three-year average of the 98th percentile for 24-hour exposure, and at 15.0 μg/m3 for annual exposure, measured as the three-year annual mean. EPA revised the air quality standards for particle pollution in 2006, tightening the 24-hour fine particle standard to 35 μg/m3 and retaining the annual fine particle standard at 15.0 μg/m3. In December 2012, EPA strengthened the annual fine particle standard to 12.0 μg/m3.

CSAPR was promulgated to help downwind states in the eastern U.S. achieve the 1997 annual average PM2.5 NAAQS and the 2006 24-hour PM2.5 NAAQS; therefore, analyses in this report focus on those standards.

Changes in PM₂.₅ Nonattainment Areas

In the eastern U.S., recent data indicate that no areas are violating the 1997, 2006, or 2012 PM2.5 NAAQS. The majority of SO2 and annual NOX emission reductions in the power sector that occurred after 2003 are attributable to the ARP, NBP, CAIR, and CSAPR. As power sector emissions are an important component of the SO2 and annual NOX emission inventory, it is reasonable to conclude that these emission reduction programs have significantly contributed to these improvements in PM2.5 air quality.

Particulate Matter Seasonal Trends

- The AQS includes average PM2.5 concentration data for 124 sites located in the CSAPR SO2 and annual NOX program region. Trend lines in PM2.5 concentrations show decreasing trends in both the warm months (April to September) and cool months (October to March) unadjusted for the influence of weather.

- The seasonal average PM2.5 concentrations have decreased by about 49 and 48 percent in the warm and cool season months, respectively, between 2000 and 2022.

Changes in PM₂.₅ Nonattainment

- Thirty six of the 39 designated nonattainment areas for the 1997 annual average PM2.5 NAAQS are in the eastern U.S. and are home to about 79 million people.7, 8 The nonattainment areas were designated in January 2005 using 2001 to 2003 data.

- Based on data gathered from 2020 to 2022, 35 of these eastern areas originally designated nonattainment have concentrations below the level of the 1997 PM2.5 standard (15.0 μg/m3), indicating improvements in PM2.5 air quality. One area has incomplete data.

Changes in 1997 Annual PM2.5 NAAQS Nonattainment Areas in CSAPR States, 2001-2003 (Original Designations) versus 2020-2022

More Information

- Clean Air Status and Trends Network (CASTNET)

- Air Quality System (AQS)

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)

- Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) Pollution

- Nitrogen Oxides (NOX) Pollution

- Ozone Pollution

- Ozone Designations

- Meteorologically Adjusted Ozone Trends

- Nonattainment Areas

- EPA’s Power Sector Programs

- EPA’s National Air Quality Trends Report

1 Katsouyanni, K., Schwartz, J., Spix, C., Touloumi, G., Zmirou, D., Zanobetti, A., Wojtyniak, B., Vonk, J.M., Tobias, A., Pönkä, A., Medina, S., Bachárová, L., & Anderson, H.R. (1996). Short term effects of air pollution on health: a European approach using epidemiologic time series data: the APHEA protocol. J. of Epidemiol Community Health, 50: S12–S18.

2 Wells, B., Dolwick, P., Eder, B., Evangelista, M., Foley, K., Mannshardt, E., Misenis, C. & Weishampel, A. (2021). Improved estimation of trends in US ozone concentrations adjusted for interannual variability in meteorological conditions. Atmospheric Environment, 248, 118234.

3 Peel, J.L., Tolbert, P.E., Klein, M., Metzger, K.B., Flanders, W.D., Todd, K., Mulholland, J.A., Ryan, P.B., & Frumkin, H. (2005). Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology, 16: 164–174.

4 Hong, C., Goldberg, M.S., Burnett, R.T., Jerrett, M., Wheeler, A.J., & Villeneuve, P.J. (2013) Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and cardiovascular mortality. Epidemiology, 24: 35–43.

5 U.S. Census. (2020).

6 40 CFR Part 81. Designation of Areas for Air Quality Planning Purposes.

7 Dockery, D.W., Speizer F.E., Stram, D.O., Ware, J.H., Spengler, J.D., & Ferris Jr., B.G. (1989). Effects of inhalable particles on respiratory health of children. American Review of Respiratory Disease 139: 587–594.

8 Schwartz, J. & Lucas, N. (2000). Fine particles are more strongly associated than coarse particles with acute respiratory health effects in school children. I 11: 6–10.

9 Bell, M.L., Dominici, F., Ebisu, K., Zeger, S.L., & Samet, J.M. (2007). Spatial and temporal variation in PM₂.₅ chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environmental Health Perspectives 115: 989–995.