Marine Species at Risk

Updated June 2021 based on data available through December 2017.

- About Marine Species at Risk

- What's Happening?

- Why Is It Important?

- Why Is It Happening?

- What's Being Done About It?

- Seven Things You Can Do To Help

- References

About Marine Species at Risk

Many marine species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and invertebrates (insects, worms, crabs, clams, etc.) have experienced serious declines and are at risk or vulnerable to extinction.

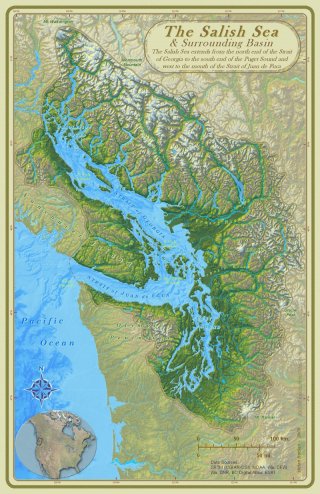

These species depend on the Salish Sea marine ecosystem (see watershed boundary map) for all or parts of their life cycle, including reproduction, migration, and molting, as well as for foraging and over-wintering.

What's Happening?

The number of species in the Salish Sea formally assessed as being at-risk or vulnerable to extinction has continued to grow since 2002.

As of December 2015, 126 marine species and sub-species were designated as being at some risk of extinction, including:

- 59 birds.

- 44 fish.

- 16 mammals.

- 5 invertebrates.

- 2 reptiles.

Four government jurisdictions share the responsibility for determining which marine species in the Salish Sea need formal protection to ensure survival. These include the Province of British Columbia, the State of Washington, the Canadian Federal Government, and the U.S. Federal Government.

Between 2011 and 2015, 17 new marine species were either designated as at-risk, or became candidates for a status assessment in at least one of the four established government jurisdictions. These species include five fishes, eight birds, one whale species, two moth species, and a species of barnacle (Table 1, Table 2).

During this same time period, 14 marine species that were previously designated as at-risk or that were candidates for a status assessment were declared as not at risk under respective jurisdictions (Table 3). Also, the increase in new marine species at-risk documented between 2011 and 2015 was smaller than the increase documented between 2008 and 2011 when 23 new marine species were identified as at risk (Table 4).

Despite these improvements, the total number of marine species at risk in the Salish Sea is now more than double the amount it was in 2002 when only 60 marine species were identified as at-risk.

Terminology

The four jurisdictions that share the responsibility of designating species as "at-risk" in the Salish Sea are the Province of British Columbia, the State of Washington, the Government of Canada, and the United States Federal Government. Throughout this indicator, the terms threatened, endangered, and species of concern are used, and it is important to note that each jurisdiction uses these terms to describe species at risk in slightly different ways. See below for a detailed description of how these terms, and others, are used in each respective jurisdiction.

Province of British Columbia

- Red List: This list includes species and ecosystems that are at the highest risk of being lost (extirpated, endangered, threatened).

- Blue List: This list includes species and ecosystems that are at a medium risk of being lost (special concern).

- Yellow List: This list includes species and ecosystems that are at a low risk of being lost.

State of Washington

- State Endangered: a species that is significantly threatened with extinction throughout all or a large portion of its range in the state.

- State Threatened: a species that is likely to become endangered in the near future unless measures are taken to protect it.

- State Sensitive: a species that is vulnerable or declining and that is likely to become threatened unless measures are taken to protect it.

- Candidate: species that are being considered to be listed as State Endangered, Threatened, or Sensitive.

Government of Canada

- Extirpated: a species that no longer exists in the wild in Canada but exists in the wild elsewhere.

- Endangered: a species that is facing imminent extirpation or extinction

- Threatened: a species that is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to protect it.

- Special Concern: a species that is likely to become threatened due to a combination of factors and threats.

- Candidate: high priority species that are to receive a status assessment to determine if they are at-risk.

United States Federal Government

- Extirpated: a species that no longer exists in a region that was once a part of its range.

- Endangered: a species in danger of extinction in the near future throughout all or a large portion of its range.

- Threatened: a species that is likely to become endangered in the near future throughout all or a large portion of its range.

- Species of concern: a species that might be in need of conservation actions. These species do not receive legal protection.

- Candidate: species for which there is enough information on their biological status to propose them as endangered or threatened but which have not been designated as such yet.

Why is it Important?

253 species of fish, 172 birds, 37 mammals, and many more invertebrate species like crabs, mussels, shrimp, and worms use the Salish Sea marine ecosystem for some part of their life cycle. Nearly 50% of these birds and 80% of these mammals depend on the ecosystem for habitat to feed, reproduce, and care for their offspring.

As of December 2015, nearly 20% of all fish species in the Salish Sea ecosystem are designated as either threatened, endangered or have new data that suggest they may be at-risk. As well, approximately 34% of all birds and 43% of all mammals that use this ecosystem are threatened, endangered or are candidates for status assessments.

The loss of species points to declining ecosystem conditions that affects the economic, social and cultural well-being of our communities. Without stronger efforts to protect and improve water quality and habitats and to conserve broader food-webs, the number and populations of local species may continue to decline.

The disappearance of marine birds and marine mammals near the top of the food chain is particularly worrisome. Levels of marine bird populations have been studied for many years to monitor impacts from pollution, detect changes in the availability of prey, and assess impacts of changes in ocean patterns.

Populations of marine birds have been declining in the Salish Sea since the 1990s. Long term monitoring has shown declines in nearly half of marine bird species (including seabirds, sea ducks, and shorebirds) that overwinter in the Salish Sea.

Wildlife observation (including whale and bird watching) has become a significant economic activity in North America, generating millions of dollars in British Columbia and Washington State each year. However, about one third (34%) of bird species and over one third (36%) of whale species in the Salish Sea are threatened, endangered, or are candidates for status assessments. If these at-risk species experience further population declines, there would likely be a decrease in wildlife observation opportunities and this would cause considerable economic losses in the region.

Further, over 50 marine species in the Salish Sea are critical to the livelihoods of the Coastal Salish First Nations and Tribes, whose peoples have lived in the region since time immemorial. These species are heavily depended upon as a food source, for harvest revenue, and for their cultural and spiritual significance.

Why is it Happening?

Many factors can play a role in the loss of species, including:

- Habitat loss and degradation due to human population growth and land use changes.

- Pollution and changes in water quality.

- Climate changes including water temperature, hydrology and acidification of marine waters.

- Overfishing and the accumulation of derelict fishing gear.

- Physical and acoustic disturbance from human sources.

Development in floodplains, wetlands and riparian areas affects many species, particularly birds and salmon. Juvenile salmon on their downstream migration are also vulnerable to changes in hydrology from urbanization and declines in water quality associated with urban stormwater runoff. Increasing water temperatures can also be lethal to salmon as they migrate along river and stream corridors.

Another key threat to fish species (e.g. Pacific herring, Pacific sand lance, and surf smelt) is the loss of spawning habitat such as kelp and eelgrass beds which can be impacted by changes to both water quality and natural shorelines. For example, shoreline armoring (the use of structures to prevent coastal erosion) contributes to declines in forage fish habitat quality, as well as population declines of invertebrate species.

Declines in marine birds can be linked to changes in availability of food sources such as Pacific herring, Pacific sardine, and surf smelt. Derelict fishing gear (such as lost or abandoned fishing nets) also poses a threat to marine birds and marine mammals which can easily become entangled and drown.

Overfishing also plays a leading role in the decline of vulnerable fish populations such as rockfish. Though government jurisdictions often limit the fishing of at-risk species, accidental and intentional noncompliance with fishing regulations can be a problem.

A variety of human-caused physical and acoustic disturbances threaten a number of marine mammals. Physical disturbances include oil spills, vessel strike risk, and the release of toxic chemical and biological contaminants from industrial discharge and urban stormwater runoff. Vessel noise is a considerable acoustic disturbance that can make it more difficult for marine mammals to locate their prey. A prime example of a marine mammal that is impacted by these disturbances is the Southern Resident Killer Whale. These animals are being threatened, particularly by declines in prey availability, excessive vessel noise, and heavy exposure to toxic pollutants. They have been designated as endangered at both the state/provincial and federal levels in Canada and the United States.

What's Being Done About It?

Governments are taking actions such as developing species recovery and management plans, carrying out scientific research and implementing management measures to support recovery, establishing catch restrictions, and creating conservation areas to help recover and maintain declining marine species.

Examples

Below are some examples of actions that government organizations, communities, Indigenous groups, tribes and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are taking:

- In March 2018, Governor Jay Inslee issued an executive order requiring state agencies to take immediate action to protect the remaining Southern Resident Killer Whales. His order established the Southern Resident Orca Task Force, to recommend the best actions to recover the southern residents. His order directs the Puget Sound Partnership and the Department of Fish and Wildlife to convene and support the Task Force.

- Supported by work under the Whales Initiative and new investments announced in October 2018, the Government of Canada is working on short and long-term management measures to support the recovery of the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whale. Since 2018, short-term management measures, such as fishing closures, and Interim Sanctuary Zones, have been implemented to help reduce the threat of reduced prey availability and physical and acoustic disturbances. Long-term management measures include conserving and rebuilding Chinook salmon populations, investing in habitat protection, and researching impacts of contaminants on whales and their prey. Development of these management measures to support the recovery of the Southern Resident Killer Whales are informed by technical working groups comprised of subject matter experts from Indigenous groups, environmental organizations, academic institutions, the shipping industry, the whale watching industry, and other levels of government.

- The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife works with partners to maintain healthy wildlife populations through a variety of planning, monitoring, recovery, and incentive programs. One such program is the recent Salish Sea Marine Survival Project, which is investigating the causes of salmon and steelhead population declines. The Pacific Salmon Foundation and Long Live the Kings are the two organizations that are co-leading this project. Other government organizations, including the Puget Sound Partnership and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, are also supporting this effort.

- Shore Friendly is an approach developed to encourage forgoing or removing shoreline armor and is grounded in social marketing research conducted in the Puget Sound. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has supported the underlying research, brand development, and pilot programs through National Estuary Program funding. In Canada, NGOs such as the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup, Surfrider Foundation Vancouver, and many others inspire citizens to clean their local shorelines, protecting marine species from the harmful impacts of marine debris.

- The Puget Sound Partnership is working with other state, local, federal and tribal programs to protect and restore local habitats including shorelines and riparian areas, estuary wetlands, eelgrass and floodplain habitats. The Sustainable Lands Strategy is an example where restoring floodplains, improving fish habitat and protecting agricultural communities from flood threats are pursued through a multi-objective approach. Read more about this project at Stories of Puget Sound Recovery: Setting the Table for Fish, Farms, and Floodplains.

- British Columbia's Ministry of Environment developed a set of science-based tools and actions, called a Conservation Framework, for conserving species and ecosystems. A centerpiece of this framework is the BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer which provides conservation information on approximately 6000 species and 600 ecological communities in British Columbia.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada has established Rockfish Conservation Areas (RCAs) to protect rockfish from recreational and commercial fisheries. Likewise, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has developed its own Puget Sound Rockfish Conservation Plan to help restore and maintain abundance, distribution, diversity and long-term productivity of rockfish populations.

- The Government of Canada supports projects by First Nations, NGOs, and other local groups that help protect and recover aquatic species at risk through the Habitat Stewardship Program and the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk. These partnerships have provided significant contributions to research, outreach, and education efforts for aquatic species at risk.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada is working to develop Marine Spatial Planning initiatives in several marine areas throughout Canada. These initiatives will bring together federal and provincial governments, Indigenous communities, and other key stakeholders to better coordinate the use and management of marine spaces. The main goal of these initiatives is to establish long-term marine planning objectives that includes shared accountability for implementation among all parties that are involved.

Learn More

- Canada Species at Risk Public Registry

- British Columbia Red, Blue and Yellow Lists

- Washington Fish and Wildlife Threatened and Endangered Species

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Environmental Conservation Online System

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs: Thriving Species and Food Web

- NOAA Southern Resident Killer Whale Recovery Planning and Implementation

Seven Things You Can Do To Help

- Help preserve our shorelines that provide critical habitat for marine and aquatic species. Volunteer on a habitat restoration project or in a community-based science program. Or clean your local shoreline.

- Use beneficial landscaping techniques such as rain gardens, rain barrels, green roofs and permeable paving to help reduce the need for chemical fertilizers and reduce runoff into ditches and storm drains.

- Keep plastics, medications, and toxic chemicals out of our waterways. Never dump into household toilets and sinks or outside where they can get into ditches or storm drains. See if your community has a household hazardous waste drop-off facility that will take your old or unused chemicals or find a medicine take-back location. Use environmentally friendly products in your home and on your landscape, fix vehicle leaks, use a commercial car wash, and have your vehicle oil changed by a professional.

- Report derelict fishing gear so that it can be safely removed to protect people and wildlife. Learn how to prevent your own gear from becoming lost. Visit the Northwest Straits Derelict Gear Program to learn more.

- Purchase sustainably-harvested seafood at your local supermarket or favorite restaurant (check for a certification symbol on food packaging or menus, such as Ocean Wise Sustainable Seafood). When fishing, be aware of relevant local and national regulations that may restrict what species or amounts you may take.

- Quiet the waters of the Salish Sea to help orcas find food. If you’re a boater, give orcas and other marine mammals space. Follow the Be Whale Wise guidelines and associated links for regulations in effect and see orca.wa.gov for links to organizations to join or support.

- Report your sightings of whales, dolphins, sharks, and porpoises and report any marine mammals in distress that you see. In British Columbia waters, report your sightings to the BC Cetacean Sightings Network. Your reports are used to track species abundance, reduce ship strikes, and contribute to science. The Orca Network, located in Washington State, also maintains a database of sightings of Killer Whales and other cetaceans sighted in the Salish Sea. In Canada, you can report marine mammal disturbance, or injured, distressed, dead, stranded, or entangled marine mammals or sea turtles to the joint Fisheries & Oceans Canada/B.C. Marine Mammal Incident Reporting 24/7 Hotline at 1-800-465-4336 or email [email protected]. In the United States, you can report marine mammal harassment to the NOAA Fisheries’ Office for Law Enforcement at 1-800-853-1964, you can report marine mammal entanglements at 1-877-707-9425, and you can report marine mammal strandings.

References

Below is a listing of references used in this report.

- Zier, J. and J. K. Gaydos. 2016. The growing number of species of concern in the Salish Sea suggests ecosystem decay is outpacing recovery. Proceedings of the 2016 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference, April 13-15, 2016, Vancouver, BC. https://www.seadocsociety.org/s/Zier-and-Gaydos-2016-Salish-Sea-Species-of-Concern-FINAL.pdf.

- Pietsch, T. W., and J. W. Orr. 2015. Fishes of the Salish Sea: A Compilation and Distributional Analysis. NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18, U.S. Department of Commerce. https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pp18.pdf.

- Gaydos, J.K. and S.F. Pearson. 2011. Birds and Mammals that Depend on the Salish Sea: A Compilation. Northwestern Naturalist 92:79-94.

- Vilchis, L. I., Johnson, C. K., Evenson, J. R., Pearson, S. F., Barry, K. L., Davidson, P., Raphael, M. G. and J. K. Gaydos. 2014. Assessing ecological correlates of marine bird declines to inform marine conservation. Conservation Biology 29(1):154-163. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/cobi.12378.

- Gaydos, J. K., Thixton, S. and Donatuto, J. 2015. Evaluating threats in multinational marine ecosystems: A Coast Salish First Nations and tribal perspective. PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144861. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144861&type=printable.

- Williams, G.D, Levin, P.S and Plasson, W.A. 2010. Rockfish in Puget Sound: An ecological history of exploitation. Marine Policy 34: 1010 - 1020.

- Lancaster, D., Dearden, P. and Ban, N. C. 2015. Drivers of recreational fisher compliance in temperate marine conservation areas: A study of rockfish conservation areas in British Columbia, Canada. Global Ecology and Conservation 4:645-657. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351989415001079/pdfft?isDTMRedir=true&download=true.

- Therriault, T.W, Hay, D.E and Schweigert, J.F. 2009. Biological overview and trends in pelagic forage fish abundance in the Salish Sea (Strait of Georgia, British Columbia). Marine Ornithology 37: 3-8. http://www.marineornithology.org/PDF/37_1/37_1_3-8.pdf.

- Dethier, M. N., Raymond, W. W., McBride, A. N., Toft, J. D., Cordell, J. R., Ogston, A. S., Heerhartz, S. M. and Berry, H. D. 2016. Multiscale impacts of armoring on Salish Sea shorelines: evidence for cumulative and threshold effects. Estuarine, Coastal, and Shelf Science 175:106-117.

- Good, T.P, June, J.A, Etinier, M.A and Broadhurst, G. 2009. Ghosts of the Salish Sea: Threats to Marine Birds in Puget Sound and the Northwest Straits from derelict fishing gear. Marine Ornithology 37: 67-76. http://www.marineornithology.org/PDF/37_1/37_1_67-76.pdf.

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2019, June). Threatened and endangered species. https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-02/statelistedcandidatespecies_02272020.pdf.

- Province of British Columbia. (2020). Red, Blue, and Yellow Lists. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/plants-animals-ecosystems/conservation-data-centre/explore-cdc-data/red-blue-yellow-lists.

- Government of Canada. (2014, October 9). Species at Risk public registry: glossary of terms. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/glossary-terms.html.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. (2015). Endangered Species Glossary. https://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/HCP_Handbook-Glossary.pdf.

- Gaydos, J. K., & Zier, J. (2014, April). Species of Concern within the Salish Sea nearly double between 2002 and 2013. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2014 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference, Seattle, Washington.

- Gaydos, J. K., & Brown, N. A. (2011). Species of Concern within the Salish Sea: changes from 2002 to 2011. Proceedings of the 2011 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference, October 25-27, 2011, Vancouver, BC.