Climate Change and the Health of Older Adults

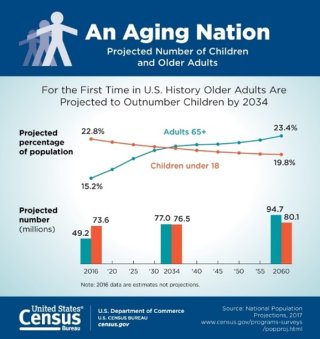

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. 2018.

There were more than 79 million older adults (60 years or older) in the United States in 2022, making up over one-fifth of the population.1 Older adults are particularly vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change because:

- As people age, our bodies are less able to compensate for the effects of certain environmental hazards, such as air pollution.2

- Older adults are more likely to have health conditions that make them more sensitive to climate hazards like heat and air pollution, which can worsen their existing illnesses.3

- Many older adults have limited mobility, increasing their risks before, during, and after an extreme weather event.4

- Aging and some medications can change the body’s ability to respond to heat. This puts older adults more at risk for heat illnesses and death as the climate warms.5

- Many older adults have compromised immune systems, which make them more prone to severe illness from insect- and water-related diseases that may become more common with climate change.6

- Older adults may depend on others for medical care and assistance with daily life, increasing their vulnerability to extreme weather events.7

Key Threats to Older Adults’ Health

In the United States, many climate-related threats affect older adults’ health. Below are some examples of the potential health impacts of these hazards.

- Heat Illnesses

- Respiratory Illnesses

- Insect- and Tick-Related Diseases

- Injuries and Deaths

- Mental Health Effects

- Water-Related Illnesses

Heat Illnesses

Heat illnesses can occur when a person is exposed to high temperatures and their body cannot cool down. Increases in average and extreme temperatures and heat waves are expected to lead to more heat illnesses and deaths among vulnerable groups, including older adults.12 Even small temperature increases may pose risks to older adults in some regions.13 Certain factors, such as preexisting medical conditions like diabetes, can further increase their risk.14

Older adults who live in cities may also be subject to the urban heat island effect, where surfaces like pavements absorb sunlight and radiate heat, making cities hotter than outlying areas.15

Respiratory Illnesses

Climate change may increase outdoor air pollutants, such as ground-level ozone and particulate matter in wildfire smoke and dust from droughts.17 Air pollution can increase the risk of heart attacks for older adults, especially those who are diabetic or obese.18 It can worsen conditions like asthma and COPD.19 Exposure to ground-level ozone can also harm lung functioning.20

Earlier spring warming, precipitation changes, and rising temperatures and carbon dioxide concentrations can increase the length and severity of the pollen season.21 Data show the ragweed pollen season is already becoming longer in some U.S. locations.22 Allergens like ragweed pollen can worsen existing respiratory conditions and contribute to the onset of asthma.

Older adults who live in buildings that are older or have poor ventilation may also be more at risk for exposure to indoor air pollutants. These pollutants can include bacteria and mold caused by water damage from extreme weather events, such as floods and storm surges.23

Older adults may be part of other groups vulnerable to climate change. This can increase their health risks. For example, some older adults can have multiple existing health conditions (such as heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and cancer) that put them at greater risk.9 Certain immigrant groups and communities of color have a greater incidences of kidney disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD).10 Older adults can also be more at risk because of social and economic factors, such as fixed incomes, living alone, and lack of support networks.11

Insect- and Tick-Related Diseases

Warmer temperatures associated with climate change can increase mosquito development and biting rates, while increased rainfall can create breeding sites for mosquitoes.25 West Nile virus, spread by mosquitoes, poses greater risks for older adults with compromised immune systems.26 Many people do not experience symptoms from West Nile virus. However, some people develop serious, and even fatal, sickness.27

Studies show that climate change has already contributed to an expanded range for ticks.28 This could put more people, including older adults, at risk of contracting Lyme disease. Adults aged 55–79 have the highest incidence rates of confirmed and probable cases of Lyme disease in the United States.29 Lyme disease can cause chronic pain and neurological problems if not treated early.30

Injuries and Deaths

Older adults often have limited mobility, making it difficult to get to safety during extreme weather events.31 Extreme events can also interrupt older adults’ medical care, making it hard for them to be transported with their correct medications, medical records, and health equipment. Power outages after a storm can also affect elevators, air conditioning or heat, and electronically powered medical equipment, making older adults particularly vulnerable.32 The National Institute on Aging has prepared a list of Emergency Kit Essentials for a Disaster.

Mental Health Effects

Extreme weather events like hurricanes, floods, and wildfires can cause emotional trauma. Older people who have cognitive disabilities like dementia can have a harder time responding to and coping with these events.34

Other climate-related hazards can also contribute to mental health effects. For example, long-term exposure to air pollution is linked with faster cognitive decline in older adults.35

Water-Related Illnesses

Climate change will impact water resources in many ways. For example, changes in water and air temperatures, heavier and longer rains, flooding, and rising sea levels can introduce disease-carrying organisms into drinking water supplies and recreational waters.37 Because many older adults have compromised immune systems, they have a higher risk for contracting gastrointestinal or other diseases from untreated contaminated water.38 Water-related diseases can often be more severe for older adults and can sometimes lead to long-term illness or even death.39

Climate change may also increase the likelihood of harmful algal blooms caused by certain types of algae and bacteria.40 Harmful algal blooms can make drinking and recreational water sources unsafe. For example, swimming in waters with a harmful algal bloom can cause respiratory illnesses and eye irritation.41 People with chronic respiratory diseases, specifically asthma, are at increased risk of illness from harmful algal blooms.42

Older adults, their families, and caretakers can take steps to decrease the health impacts of climate change. Consider the following action items:

- Stay cool and hydrated. Drink enough water. Wear loose, light-colored clothing, and stay in air-conditioned spaces as much as possible. If you don’t have an air conditioner, reach out to your friends and family. Know if there are public cooling centers in your community.

- Stay informed about air quality. Use AirNow to check local air pollution levels and make informed choices about outdoor activities and possible health impacts.

- Prevent bites. Use insect repellents to help avoid tick and bug bites. You can also take steps to help reduce mosquitoes inside and outside your home.

- Make a plan. Create an emergency supply kit with medical equipment and records, food, water, and a first-aid kit. Set up a support network and update your family, friends, and caretakers on your whereabouts.

- Check in with neighbors, friends, and family. If you know someone who lives in an assisted living or senior housing facility, be sure they have emergency supplies, a plan for shelter, and transportation during extreme weather events. Check in with elderly loved ones or neighbors, particularly if they live alone and have health conditions that could put them at risk during or after an extreme weather event.

- Be aware of your local community resources. Many local senior services agencies provide shelter and transportation resources for older adults during extreme weather. If you have a disability, contact your local emergency management office to see if you can get assistance during an emergency.

Related Resources

EPA resources:

Other resources:

Endnotes

1 U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Population 60 Years and Over in the United States. American Community Survey. Retrieved 10/18/2024.

2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Older adults and air quality. Retrieved 3/11/22.

3 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

4 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 257.

5 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

6 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

7 Bell, J.E., et al. (2016). Ch. 4: Impacts of extreme events on human health. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 104.

8 U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). Older people projected to outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history. Retrieved 3/11/2022.

9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Chronic disease indicators: older adults. Retrieved 9/25/2024.

10 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 252.

11 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 257.

12 Crimmins, A., et al. (2016). Executive summary (pdf) (10 MB). In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 8.

13 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The Impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 257.

14 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

15 Chu, E.K. et al. (2023). Ch. 12: Built Environment, Urban Systems, and Cities. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 12-12.

16 EPA. (2021). Climate change indicators: Heat-related illnesses. Retrieved 3/11/2022.

17 West, J.J. et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air Quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

18 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 257.

19 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 257.

20 West, J.J. et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air Quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

21 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 526.

22 West, J.J. et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air Quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-14.

23 West, J.J. et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air Quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-14.

24 CDC. (2021). Most recent national asthma data. Retrieved 10/31/2024.

25 Hayden, M.H. et al. (2023). Ch. 15: Human Health. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 15-8.

26 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

27 CDC. (2021). West Nile virus. Retrieved 3/11/2021.

28 Hayden, M.H. et al. (2023). Ch. 15: Human Health. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 15-8.

29 CDC. (2024). Lyme disease surveillance data. Retrieved 7/16/2024.

30 CDC. (2024). Signs and symptoms of untreated Lyme disease. Retrieved 7/16/2024.

31 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

32 Bell, J.E., et al. (2016). Ch. 4: Impacts of extreme events on human health. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 105.

33 Louisiana Department of Health. (2021). Hurricane Ida storm-related death toll rises to 26. Retrieved 3/11/2022.

34 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

35 Dodgen, D., et al., (2016). Ch. 8: Mental health and well-being. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 225.

36 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

37 Crimmins, A., et al. (2016). Executive summary (pdf) (10 MB). In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 6.

38 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

39 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

40 Trtanj, J., et al. (2016). Ch. 6: Climate impacts on water-related illness. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 160-169.

41Trtanj, J., et al. (2016). Ch. 6: Climate impacts on water-related illness. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 165.

42 Trtanj, J., et al. (2016). Ch. 6: Climate impacts on water-related illness. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 165.