Climate Change Impacts on Air Quality

Overview

Clean air is critical to human health. It is also important for the health of vegetation and crops.1 It contributes to people’s enjoyment of scenic areas, like national parks and wilderness areas.

The effects of climate change on air quality will continue to vary by region. In many areas of the United States, climate change is expected to worsen harmful ground-level ozone, increase people’s exposure to allergens like pollen, and contribute to worsening air quality.2 It can also decrease visibility so that it is harder to see into the distance.3 Changes in the amount of outdoor air pollutants can also affect indoor air quality.

-

Increased ozone. The 10 warmest years on record have occurred within the past decade (2014-2023), with record highs across the globe in 2023.27 Temperatures are expected to continue rising, and hot, sunny days can increase the amount of ozone at ground level.

-

Increased Particulate Matter. In 2021, the U.S. Southwest experienced one of the most severe long-term droughts of the past 1,200 years.28 Dust from droughts can increase particulate matter and cause air quality issues.

-

Increased indoor pollutants. Extreme weather, such as flooding and storm surge, can damage buildings and allow water or moisture inside. Damp indoor conditions can lead to the growth of harmful pollutants, such as mold and bacteria.29

-

Increased wildfires. In 2020, wildfires burned over 10 million acres of land in the United States, the highest-ever amount on record.30 Wildfire smoke lowers air quality and harms human health.

-

Increased pollen. Rising temperatures and higher carbon dioxide concentrations related to climate change can lengthen the pollen season and increase the amount of pollen produced by plants.31

Climate impacts on air quality will depend on what additional measures are taken to reduce air pollution. Regulatory initiatives, partnership programs, and individual actions can all help reduce air pollutants that harm human health, as well as greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

Explore the sections on this page to learn more about climate impacts on air quality:

- Top Climate Impacts on Air Quality

- Air Quality and the Economy

- Environmental Justice and Equity

- What We Can Do

- Related Resources

Top Climate Impacts on Air Quality

Climate change may affect air quality at both local and regional scales. Three key impacts are described in this section.

1. Outdoor and Indoor Air Pollution

Nearly 102 million people in the United States live in areas with poor air quality in 2021.5 In many regions of the United States, climate-driven changes in weather conditions, including temperature and precipitation, are expected to increase ground-level ozone and particulate matter (such as windblown dust from droughts or smoke from wildfires).6 These changes worsen existing air pollution. Exposure to these pollutants can lead to or worsen health problems, such as respiratory and heart diseases.

Climate change can also affect indoor air quality. Increases in outside air pollutants, such as ozone and particulate matter, could lead to higher indoor exposures.7 These pollutants can enter a building in many ways, including through open doors and windows and ventilation systems.

Mold, dust mites, bacteria, and other indoor pollutants may increase as climate change-related precipitation and storms increase. For example, flood damage can create a damp indoor environment, leading to mold growth.8 Indoor air pollutants have been linked to heart disease, respiratory diseases such as asthma, and cancer.9

Air pollution may also damage crops, plants, and forests.11 For example, when plants absorb large amounts of ground-level ozone, they experience reduced photosynthesis, slower growth, and higher sensitivity to diseases.12

2. Wildfire Smoke

Climate change has already led to more frequent wildfires and a longer wildfire season.13 Wildfire smoke pollutes the air, impairing visibility and disrupting outdoor activities. It can also spread hundreds of miles downwind to other regions.

Exposure to wildfire smoke can worsen respiratory illnesses, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and bronchitis. Wildfire smoke exposures have also been linked to premature births.14

3. Airborne Allergens

A changing climate is expected to cause earlier and longer springs and summers, warmer temperatures, precipitation changes, and higher carbon dioxide concentrations. All of these changes can increase people’s exposure to pollen and other airborne allergens, which in turn can lead to more allergy-related illnesses, such as asthma and hay fever.15

For more specific examples of climate change impacts in your region, please see the National Climate Assessment.

Air Quality and the Economy

Cleaner air is closely linked to a healthy economy. For example, good air quality improves Americans’ health and productivity. In 2020 alone, reductions in air pollution prevented more than 230,000 premature deaths, 200,000 heart attacks, 120,000 emergency room visits, and 17 million lost workdays.16 Working toward cleaner air also creates jobs, advances technologies, and produces billions of dollars for the United States in revenues and exported goods and services.

Environmental Justice and Equity

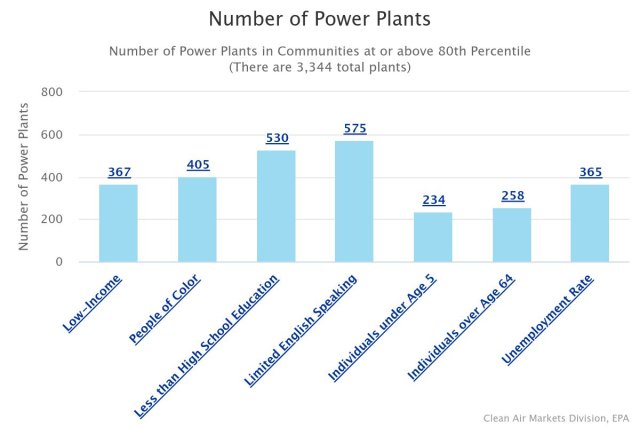

Many socially vulnerable groups live in industrial or urban areas with high levels of air pollution.17,18 In fact, Black and African Americans individuals are 34% more likely than non-Blacks to live in areas with the highest projected increases in childhood asthma due to climate-related changes in particulate matter.19 Some people are also more vulnerable to the health impacts of air pollution because they have chronic medical conditions. For example, certain communities of color, low-income groups, Indigenous populations, and immigrant groups have higher rates of heart disease, asthma, and COPD.20,21

Certain populations may also be more vulnerable to air quality impacts because they work outside. For example, farm workers, firefighters, roofers, and construction workers are among those workers whom scientists expect will be affected by air quality impacts from climate change.22

Both rural and urban low-income populations may live in older buildings that are not well sealed, increasing their exposure to outdoor allergens and pollutants.23 Older buildings or buildings in poor condition may also take more damage during extreme weather, such as storms and floods. This can lead to damp indoor environments prone to mold, bacteria, and other indoor air contaminants.24

What We Can Do

We can reduce climate and air quality impacts in many ways, including the following:

- Go green. Switch to green power from renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower to reduce both air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Reduce air pollution from vehicles. Walking, biking, and taking public transit among other actions can reduce emissions from transportation. These choices can also provide other benefits, such as safer streets.

- Improve air quality at ports. Communities situated near ports—which often include low-income and minority populations—are at a higher risk of air pollution exposure. Communities and stakeholders can work with EPA’s Ports Initiative to improve environmental performance and advance clean technologies at ports. This effort helps people living near ports breathe cleaner air. Check out the Community-Port Collaboration Toolkit for ways communities can get involved.

- Develop urban forests. Planting trees, especially in urban areas and along roads or highways, can help improve air quality. Trees also provide other benefits, such as reducing the impact of urban heat islands.

- Prevent wildfires. Pay attention to weather and drought conditions. Avoid activities involving fire or sparks when it’s dry, hot, and windy to help prevent wildfires.

- Reduce your exposure. Use the Air Quality Index (AQI) to guide outdoor activities. When you see that the AQI is unhealthy, take simple steps to reduce your exposure like choosing less intense activities, take more breaks, and reschedule activities to a time when outdoor air quality is better.

- Improve indoor air quality. Reduce or remove sources of indoor air pollutants whenever possible. For example, consider using portable air purifiers or high-efficiency filters in your heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems.

Related Resources

- Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 14: “Air Quality.”

- Air Topics. Describes how air quality can affect your health and how EPA is working to protect air quality.

- AirNow Air Quality Index. Provides daily information on how clean or polluted your outdoor air is, along with associated health impacts.

- Air Quality Resources for Tribes. Gathers Tribal-related resources from across the federal landscape into a single resource. Includes regulatory, policy, planning, guidance, and other materials for tribes to use.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: About Air Quality. Provides information and resources on air quality with additional details about specific respiratory ailments.

- Environmental Justice Grants and Resources. Manages programs that support communities as they develop solutions to address environmental and health issues, including air quality.

- Drought.gov. Shows current drought conditions in the United States and locations of active wildfires. Developed through a multi-agency partnership.

- EPA’s Heart Healthy Toolkit. Provides information on the link between air quality and heart disease, as well as steps individuals can take to protect their health.

Endnotes

1 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

2 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5, 14-14.

3 C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 519.

4 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 518.

5 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

6 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

7 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 516.

8 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-14.

9 EPA. (2021). Indoor air quality. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

10 EPA. (2021). Mold and health. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

11 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-5.

12 EPA. (2022). Ecosystem effects of ozone pollution. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

13 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-9.

14 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 518–519.

15 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-14.

16 EPA. (2022). The Clean Air Act and the economy. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

17 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-11.

18 EPA. (2022). Research on health effects from air pollution. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

19 EPA. (2021). Climate change and social vulnerability in the United States: A focus on six impacts. EPA 430-R-21-003, pp. 24—25.

20 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 252.

21 EPA. (2021). Power plants and neighboring communities. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

22 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 258.

23 Fann, N., et al. (2016). Ch. 3: Air quality impacts. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 82–83.

24 EPA. (2021). Indoor air quality (IAQ). Retrieved 3/18/2022.

25 EPA. (2024). Power plants and neighboring communities. Retrieved 1/13/2025.

26 U.S. Energy Information Administration. Renewables became the second-most prevalent U.S. electricity source in 2020. Retrieved 3/18/2022.

27 Lindsey, R., & L. Dahlman. (2024). Climate change: Global temperature. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

28 Mankin, J.S., et al. (2021). NOAA Drought Task Force report on the 2020–2021 southwestern U.S. drought. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Drought Task Force; NOAA Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections Programs; and National Integrated Drought Information System. Retrieved 5/11/2022.

29 EPA. (2021). Indoor air quality (IAQ). Retrieved 3/18/2022.

30 National Centers for Environmental Information. (2024). Annual 2023 wildfires report. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

31 West, J.J., et al. (2023). Ch. 14: Air quality. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 14-14.