Climate Change Indicators: Length of Growing Season

This indicator measures the length of the growing season in the contiguous 48 states.

Key Points

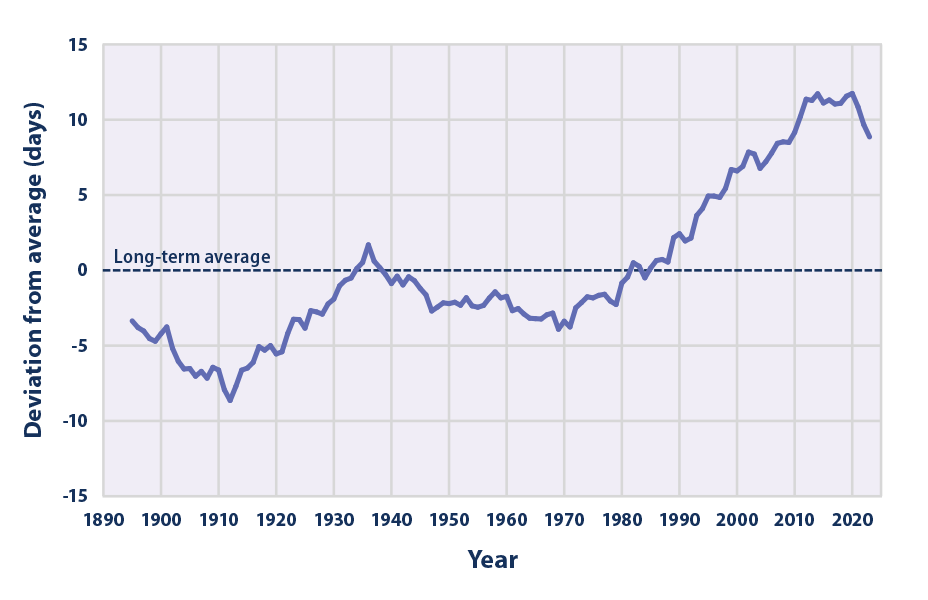

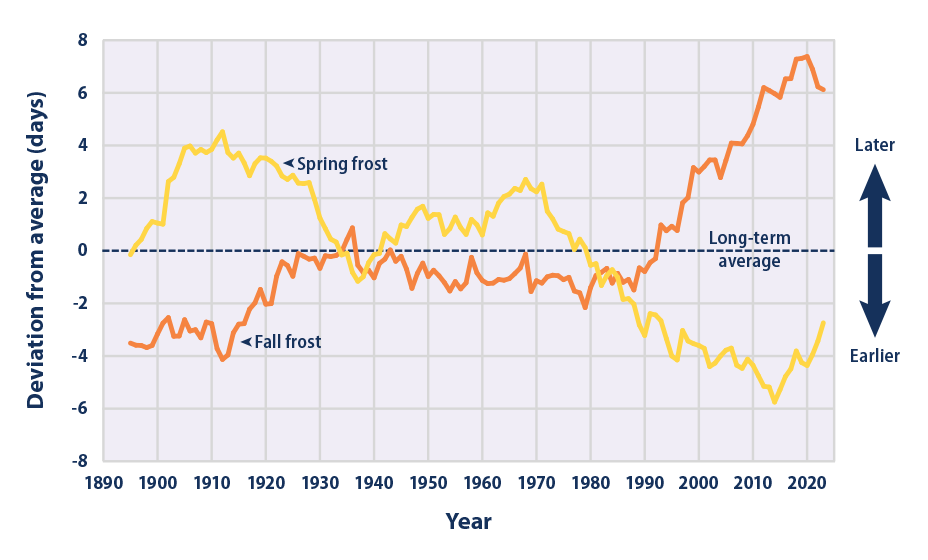

- The average length of the growing season in the contiguous 48 states has increased by more than two weeks since the beginning of the 20th century. A particularly large and steady increase has occurred since the 1970s (Figure 1).

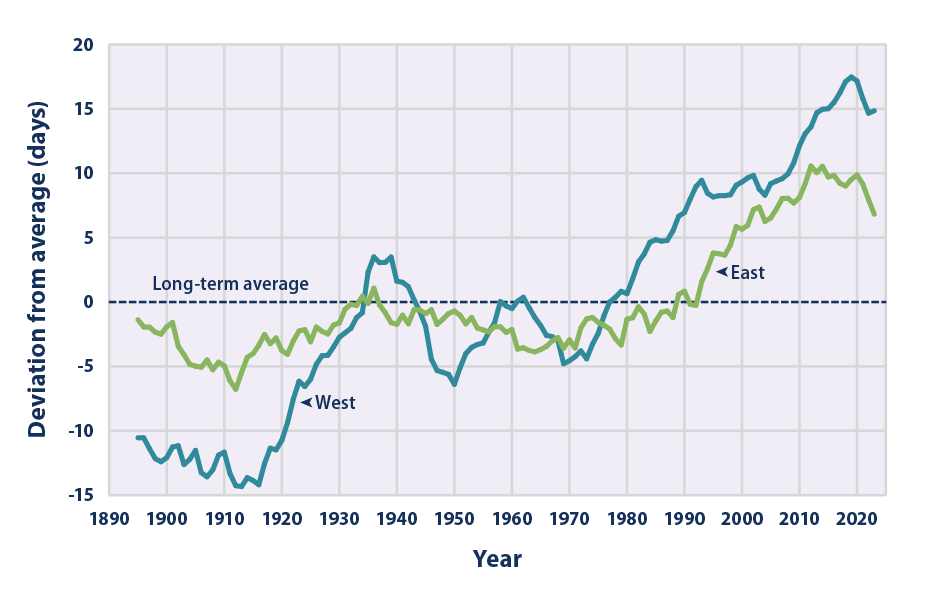

- The length of the growing season has increased more rapidly in the West than in the East. In the West, the length of the growing season has increased at an average rate of about 2.2 days per decade since 1895, compared with a rate of nearly one day per decade in the East (Figure 2).

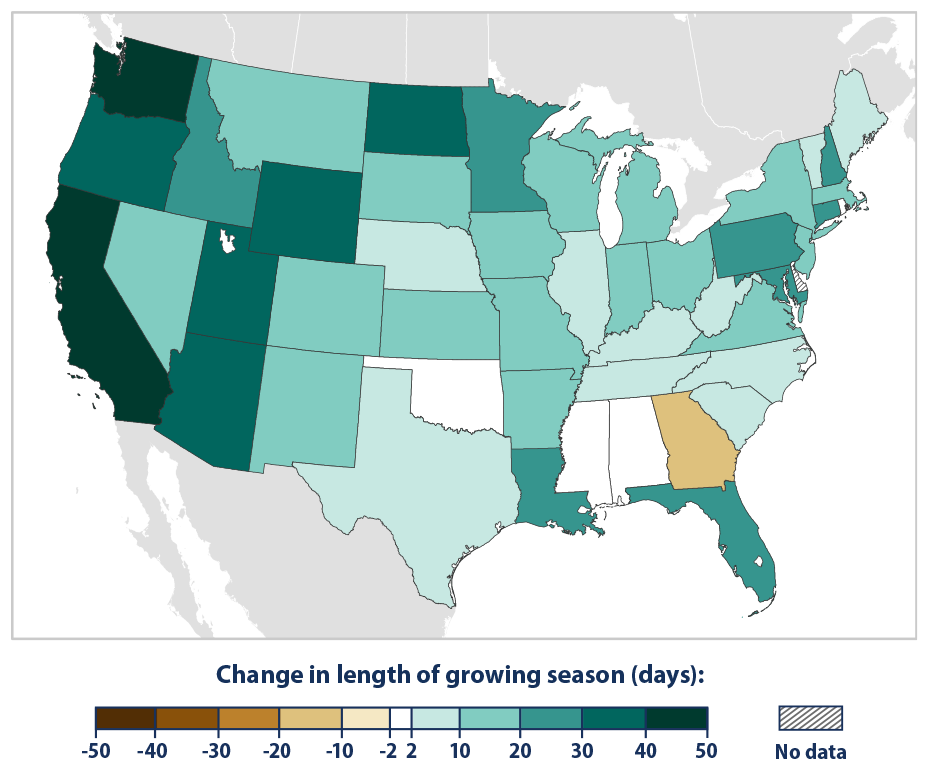

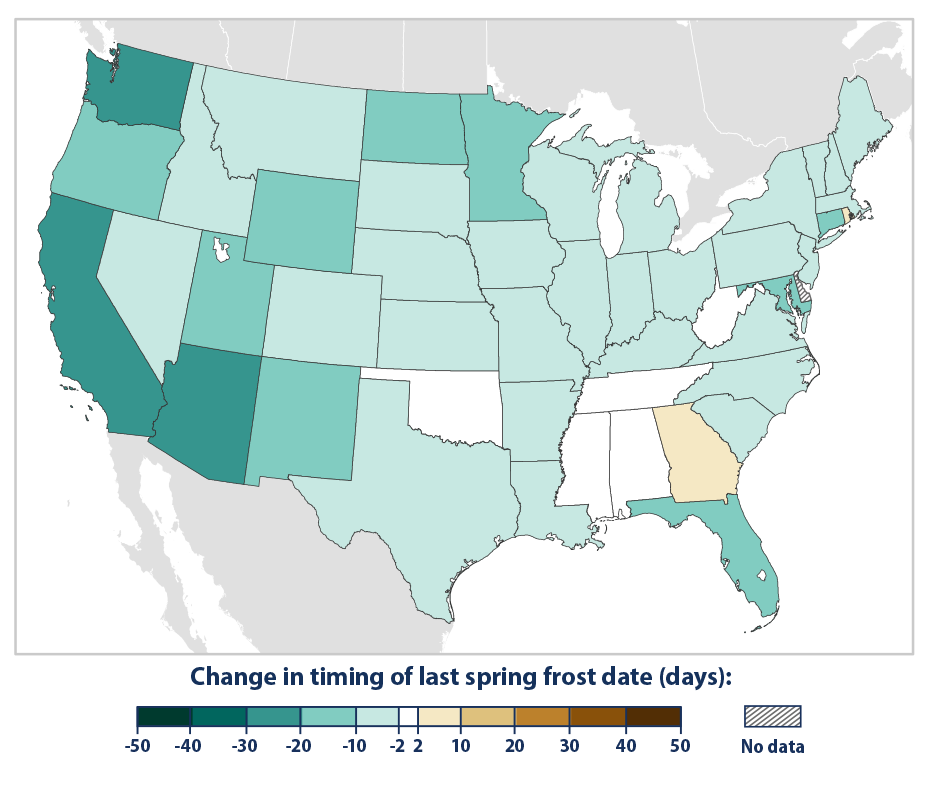

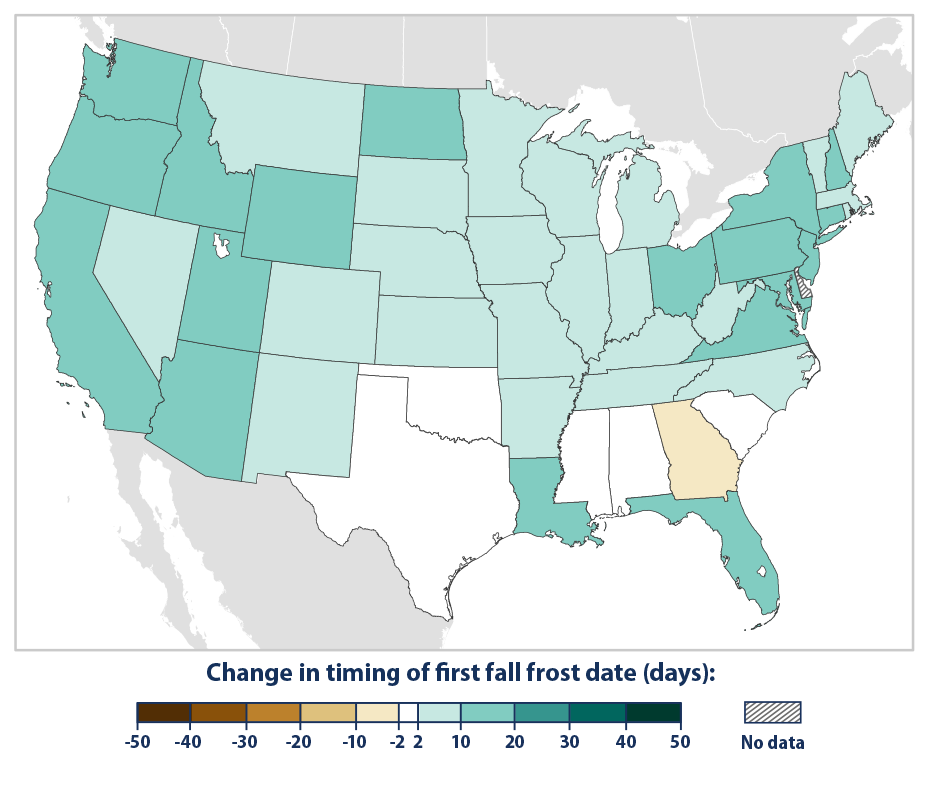

- The length of the growing season has increased in almost every state. States in the West (e.g., California and Washington) have seen the most dramatic increase. In contrast, the growing season has become slightly shorter in Georgia (Figure 3).

- In recent years, the final spring frost has been occurring earlier than at any point since 1895, and the first fall frost has been arriving later. Since 1980, the last spring frost has occurred an average of more than three days earlier than the long-term average, and the first fall frost has occurred about three days later (Figure 4).

- Patterns in the timing of spring and fall frost (Figures 5 and 6) largely mirror the overall patterns in the length of growing season (Figure 3). States that saw an increased length of growing season had comparable changes in frost-free days for both the spring and fall.

Background

The length of the growing season in any given region refers to the number of days when plant growth takes place. The growing season often determines which crops can be grown in an area, as some crops require long growing seasons, while others mature rapidly. Growing season length is limited by many different factors. Depending on the region and the climate, the growing season is influenced by air temperatures, frost days, rainfall, or daylight hours.

Changes in the length of the growing season can have both positive and negative effects on the yield and prices of particular crops. Overall, warming is expected to have negative effects on yields of major crops, but crops in some individual locations may benefit.1 A longer growing season could allow farmers to diversify crops or have multiple harvests from the same plot. However, it could also limit the types of crops grown, encourage invasive species or weed growth, or increase demand for irrigation. A longer growing season could also disrupt the function and structure of a region’s ecosystems and could, for example, alter the range and types of animal species in the area.

About the Indicator

This indicator looks at the impact of temperature on the length of the growing season in the contiguous 48 states, as well as trends in the timing of spring and fall frosts. For this indicator, the length of the growing season is defined as the period of time between the last frost of spring and the first frost of fall, when the air temperature drops below the freezing point of 32°F. This is referred to as the frost-free season. This indicator complements the Growing Degree Days indicator, which is also based on specific temperature thresholds, as well as the Freeze-Thaw Conditions indicator, which focuses on changes in the number of days the ground is frozen or unfrozen. Changes in growing season have been calculated using temperature data from 597 weather stations throughout the contiguous 48 states. These data were compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information. Growing season length and the timing of spring and fall frosts were averaged across the nation, then compared with long-term average numbers (1895–2023) to determine how each year differed from the long-term average.

About the Data

Indicator Notes

Changes in measurement techniques and instruments over time can affect trends. This indicator includes only data from weather stations with a consistent record of data points for the time period. Methods for producing state, regional, and national values by year were designed to provide spatial representativeness regardless of station density.

Data Sources

All six figures are based on temperature data compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information, and these data are available online at: www.ncei.noaa.gov. Analysis of frost timing and growing season length was provided by Kunkel (2024).2

Technical Documentation

References

1 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2022). Climate change 2022—Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

2 Kunkel, K. E. (2024). Update to data originally published in: Kunkel, K. E., Easterling, D. R., Hubbard, K., & Redmond, K. (2004). Temporal variations in frost‐free season in the United States: 1895–2000. Geophysical Research Letters, 31(3), L03201. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018624

3 Kunkel, K. E. (2024). Expanded analysis of data originally published in: Kunkel, K. E., Easterling, D. R., Hubbard, K., & Redmond, K. (2004). Temporal variations in frost‐free season in the United States: 1895–2000. Geophysical Research Letters, 31(3), L03201. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018624