A Closer Look: The Black Guillemots of Cooper Island

This feature explores changes in bird populations on an island along Alaska’s Arctic northern coast.

Key Points

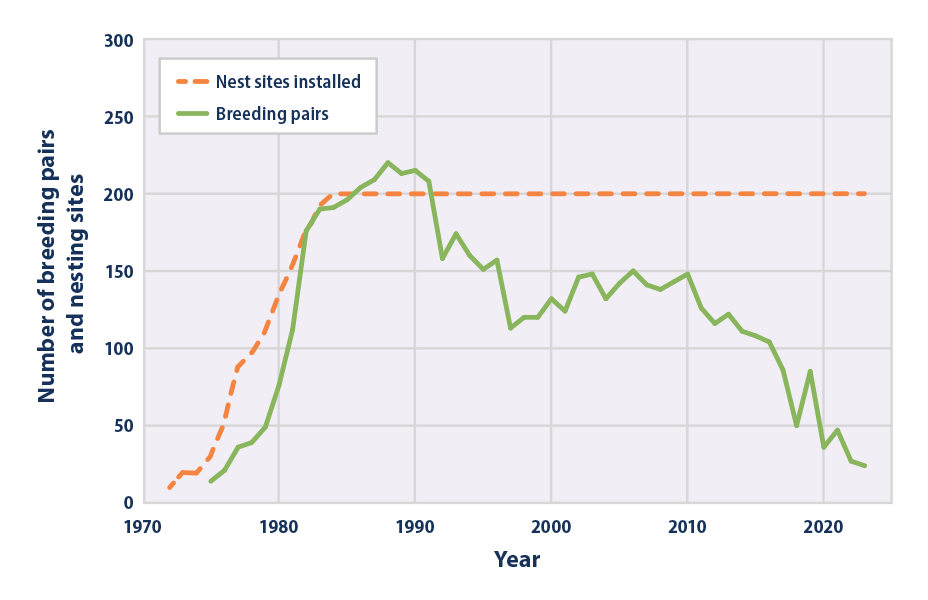

- The black guillemot population on Cooper Island reached a peak of more than 200 pairs in the late 1980s, but the number has decreased by more than 80 percent since then (see Figure 1). In 2023, scientists observed only 24 breeding pairs.

- Although the initial increase in breeding pairs coincided with an expansion of available nesting sites, the decrease since the 1980s has occurred despite a constant number of nesting sites.

- The decline over the last three decades has coincided with reduced breeding success,2 earlier egg laying,3 and a decrease in the presence of sea ice in the region,2,5 (see the Arctic Sea Ice indicator).

- Data from another long-studied colony on the edge of the Beaufort Sea (Herschel Island, Canada) suggest that similar trends are occurring across the western Arctic region.6

Background

A colony of black guillemots have made Cooper Island near Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska, home for at least 50 years. The area’s unique landscape and sea ice are integral components of this bird’s habitat. The black guillemot spends the winter on Arctic sea ice, and it breeds on land near the edge of the ice in summer.1 One of the primary food sources for the birds’ chicks is the Arctic cod, which thrives in cold, ice-covered waters. Warming temperatures and other changes are reducing the extent and persistence of Arctic sea ice (see the Arctic Sea Ice indicator), which has been linked to a decline in the abundance of Arctic cod over the last few decades.2

The region has experienced an increase in the number of days without snow cover each year.3 This longer period has helped the black guillemots during breeding season, when they prefer a snow-free nest cavity.3 However, as the Arctic has warmed, sea ice has decreased significantly—melting earlier and freezing later.4 This change, for certain parts of the year, has led to more open water and increased the distance from the coast to the edge of the ice, where these birds forage for Arctic cod.2 This type of ecosystem change has broader implications not only for these two species, but also for other animals in the Arctic that depend on marine prey, such as polar bears, and for people who depend on Arctic animals for food and other resources.

A group of scientists and volunteers have been observing and counting birds at the Cooper Island colony for almost 50 years. Birds are counted every summer and identified as breeding pairs if two are found to be inhabiting a specific nesting site on the island. This long-term record provides valuable clues about how rapid changes being observed in the Arctic may be influencing the natural environment.

For this and other examples of community connections to observed climate-related changes, see the StoryMap at: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/ebd8dcbb0b6048cd81caa6eb450b8974.

About the Data

Notes

Changes in the number of breeding pairs in the Cooper Island colony can be influenced by several factors other than the presence or absence of sea ice and resulting reduced prey availability. These other factors include competition from other bird species, the activity of predators such as polar bears, and the success of and immigration from other black guillemot colonies in the Arctic. The timing and duration of the breeding season can also change in response to changing temperatures and snow and ice conditions. In addition, as the count of breeding pairs depends on the observation of successful egg laying, changes in fertility or nest predation could influence annual totals. Consistent methods have been used to count the number of breeding pairs on Cooper Island annually for more than 40 years. Guillemots began breeding at Cooper Island sometime after the U.S. Navy left wooden boxes on the island in the mid-1950s, which the birds used for nesting. The colony was officially discovered by researchers in 1972, when it consisted of 10 breeding pairs.13 The researchers began building artificial nest sites, adding 190 sites before they stopped in the mid-1980s. Cooper Island had more breeding pairs than nest sites in the late 1980s, when some of the larger nesting sites were occupied by more than one pair. Additional birds were present but were unable to breed due to the limited number of nest cavities.

Data Sources

The data in this feature are collected by researchers and provided by George Divoky and the Friends of Cooper Island (https://cooperisland.org/). This data set has been used and published as part of peer-reviewed journal articles on observed changes in northern Alaska—particularly the region near Utqiagvik.2,3

Technical Documentation

References

1. Divoky, G. J., Douglas, D. C., & Stenhouse, I. J. (2016). Arctic sea ice a major determinant in Mandt’s black guillemot movement and distribution during non-breeding season. Biology Letters, 12(9), 20160275. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0275

2. Divoky, G. J., Lukacs, P. M., & Druckenmiller, M. L. (2015). Effects of recent decreases in arctic sea ice on an ice-associated marine bird. Progress in Oceanography, 136, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2015.05.010

3. Cox, C. J., Stone, R. S., Douglas, D. C., Stanitski, D. M., Divoky, G. J., Dutton, G. S., Sweeney, C., George, J. C., & Longenecker, D. U. (2017). Drivers and environmental responses to the changing annual snow cycle of northern Alaska. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 98(12), 2559–2577. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0201.1

4. Huntington, H. P., Strawhacker, C., Falke, J., Ward, E. M., Behnken, L., Curry, T. N., Herrmann, A. C., Itchuaqiyaq, C. U., Littell, J. S., Logerwell, E. A., Meeker, D., Overbeck, J. R., Peter, D. L., Pincus, R., Quintyne, A. A., Trainor, S. F., & Yoder, S. A. (2023). Chapter 29: Alaska. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH29

5 .USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program). (2017). Climate science special report: Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4), volume I (D. J. Wuebbles, D. W. Fahey, K. A. Hibbard, D. J. Dokken, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock, Eds.). https://doi.org/10.7930/J0J964J6

6. Eckert, C. D. (2018). Black guillemot population monitoring at Herschel Island–Qikiqtaruk Territorial Park, Yukon: Outcome of the 2018 nesting season. Yukon Department of Environment.

7. Divoky, G. J. (2024). Update to data originally published in Divoky, G. J., Lukacs, P. M., & Druckenmiller, M. L. (2015). Effects of recent decreases in arctic sea ice on an ice-associated marine bird. Progress in Oceanography, 136, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2015.05.010

8. Divoky, G. J., Watson, G. E., & Bartonek, J. C. (1974). Breeding of the black guillemot in Northern Alaska. The Condor, 76(3), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.2307/1366350

This figure shows the number of breeding pairs in the black guillemot colony that inhabits Cooper Island along the north coast of Alaska, measured at the peak of breeding season (green line). The dashed orange line indicates the number of installed nest site structures available to black guillemots on Cooper Island each year.

This figure shows the number of breeding pairs in the black guillemot colony that inhabits Cooper Island along the north coast of Alaska, measured at the peak of breeding season (green line). The dashed orange line indicates the number of installed nest site structures available to black guillemots on Cooper Island each year.